Plot:

The only person alive who remembers Luella Miller is Lydia Anderson, now eighty years old. She never thought Luella was pretty, though her husband Erastus worshipped the ground she walked on. Luella came to teach school but didn’t do much of the teaching. The work was left to one of the older girls, Lottie Henderson, who was happy to teach while Luella sat and embroidered a pocket handkerchief.

Lottie began to fade, but she kept coming to school right to the end. No one ever knew what she died of.

Luella quit teaching when she and Erastus married. Erastus did all the cooking and cleaning; he was happy to do it for his Luella. No one saw the consumption coming on nor realized how quickly it would take such a young man.

Thoughts:

Lydia compares Luella to a willow; she’s pliant and weak but unbreakable. People happily rush to care for her, as if she can’t care for herself, even at their own expense. Luella flourishes as her caretaker of the moment fades away.

How much of this does she realize? It’s hard to say. When Lydia tells her to shift for herself, she insists she can’t. Some commentators online refer to her as a “Marxist vampire.” She seems to suck the vitality out of people.

I confess I’m the first to pick up a torch or a pitchfork for the proletariat, but what strikes me about Luella is that she is a child, a dependent toddler in an adult’s body. She has never faced or overcome challenges, nor has anyone taught her practical skills. She misses the people who die, of course. But more importantly, who will take care of her now? Could she even brew herself a cup of coffee? Left to her own devices, she would starve.

Lydia tells her that Maria, the caretaker of the moment, should “stay home and do her washin’ instead of comin’ over here and doin’ YOUR work, when you are just as well able, and enough sight more so, than she is to do it?”.

Luella regards Lydia like “a baby who has a rattle shook at it. She sort of laughed as innocent as you please. ‘Oh, I can’t do the work myself, Miss Anderson,’ says she. ‘I never did. Maria HAS to do it.’”

Why Luella has been kept a child, the reader is never told. She is not wealthy—she was a schoolteacher who married a man who chopped wood for a living.

An air of the supernatural hangs on in that even after Luella dies, her menace remains.

This is a sad little horror tale.

This story can be read here:

This story can be listened to and read here: (41:07)

Bio: Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (1852-1930) began writing children’s literature as a teenager. Most of her two hundred stories for adults are realistic, such as “A New England Nun.” She also wrote ghost and supernatural stories.

Title: “Luella Miller”

Author: Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (1852-1930)

First published: Everybody’s Magazine, December 1902

Length: short story

Review of “Lot No. 249” by Arthur Conan Doyle: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

Jephro Hastie, a student at “Old College” at Oxford, is visiting with his friend, medical student Abercrombie Smith, in the latter’s third-floor turret room. Hastie warns him about the student in the room below his, Edward Bellingham.

“There’s something damnable about him. My gorge always rises around him. I should put him down as a man with secret vices.”

He continues, saying Bellingham is a “demon” at “Eastern languages,” speaking (among others) Coptic, Hebrew, and Arabic. The “demon” Bellingham is also a good friend of William Monkhouse Lee, who lives below him on the ground floor and is a friend of a mutual friend of Hastie.

“You can’t know [Lee] without knowing Bellingham,” Hastie says. Bellingham is engaged to Lee’s younger sister. Hastie describes the match as a “toad and a dove.”

Okay, Jephro, how do you really feel about him?

One night, a scream arises from Bellingham’s room. Medical student Smith runs down to see if he can be of help. He finds Bellingham in a faint. Odd Egyptian artifacts, including a mummified crocodile and a newly acquired human mummy, fill the room. It’s designated by the auctioneer’s mark, Lot 249.

Lee is with Bellingham and explains that he’s obsessed with such things.

Smith revives Bellingham (brandy is apparently useful for such revivals), who seems nervous and embarrassed, locking a yellowed scroll in a drawer.

Over the next few days, Smith hears shuffling and footsteps in Bellingham’s room when he knows his downstairs neighbor has gone out.

Someone or something jumps out of a tree and attacks a student with whom Bellingham has had a long-standing feud. The student doesn’t see the assailant.

Hmmm… could it be…?

Thoughts:

The suspense builds nicely in this story. The oddball downstairs neighbor who studies suspicious things (not medicine or classics, like the normal red-blooded undergrad), the cries, the embarrassed behavior—what is he covering up?—the charm offensive that alternates with naked aggression. Only people who had a beef with Bellingham get attacked or end up in the river.

Although it begins a bit slowly with some interminable scene-setting, this is an enjoyable little tale. Our hero may be a little slow on the uptake, but once he’s clued in, he’s all in a righteous lather. It’s fun to watch.

The reader sees the mummy in its case in Bellingham’s room (ICK), but when it’s out wreaking havoc (…perhaps…), it seems camera-shy. The opening lines set a tone of uncertainty regarding what actually happened and provide the reader with a date of May 1884, some twelve years before the story was published.

The slang places the reader in an informal college setting. When Bellingham tells Smith he’ll soon leave his rooms and let him study, he says, “Three whiffs of baccy, and I am off.”

Come on, guy. That stuff will kill you, ya know.

Another idiom I had to look up. Smith, in an attempt to avoid visits from Bellingham, “sported his oak.” Apparently, it was common for college rooms in those hoary days of yore to have an inner and an outer door. The outer was often oak. If you wanted to be left alone to study, sleep, or avoid your crazy downstairs neighbor, you closed the outside door or “sported the oak.”

One can’t help wondering if Doyle weren’t remembering his own college days, studying for his medical degree—minus the downstairs neighbor reanimating mummies, of course.

I would be remiss if I didn’t note that the story is written with young men in mind. There are no women in it. Only Lee’s sister Eveline, the “dove,” is mentioned, but she never appears.

The story is one of the first to feature an evil, reanimated mummy, thus spawning a whole army of wrapped critters of the night. Forty years later, Boris Karloff would thump and strangle his way to a lot of startled faces and bloodshed.

While this might be a little slow to start and hold more surprises for the MC than for the reader, I liked it.

Bio: Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) was a British author and physician. He is best known for creating the detective Sherlock Holmes, whose deductive reasoning solved many otherwise unsolvable cases. Holmes remains one of the most popular detectives and has become the subject of many books, plays, and movies. Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes book, A Study in Scarlet, was published in 1887. Unlike Holmes, Doyle was a believer in the supernatural. He also wrote some fantasy, such as The Lost World.

This story can be read here:

This story can be listened to here: (1:26:26)

Title: “Lot No. 249”

Author: Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

First published: Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, September 1892

Length: novelette

Review of “The Kit-Bag” by Algernon Blackwood: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

The successful defense of John Turk, a client of the great Arthur Wilbraham, KC, brings the barrister no joy. His private secretary, Johnson, is glad to be rid of the case. Despite the verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity, he agrees with the general sentiment that few men were more deserving of the gallows. He tells his boss that he’s happy to see the last of John Turk’s dreadful face.

“It positively haunted me. That white skin, with black hair brushed low over the forehead, is a thing I shall never forget, and that description of the way the dismembered body was crammed and packed with lime into that—”

Wilbraham advises him not to dwell on the case but to enjoy his planned vacation to the Alps.

Johnson then asks to borrow one of Wilbraham’s kit bags (duffel bag). The latter agrees. His servant will bring it around to the secretary’s lodgings later.

When Johnson receives it, he notices that it looks a little worse for wear, but doesn’t think much about it. He begins packing, looking forward to the fresh mountain air, away from the sleet storm London is presently enduring.

It’s a little hard to tell, but he thinks he hears footsteps in the unoccupied rooms below his. Nah—just the storm. The trial must have really gotten to his nerves.

Thoughts:

Poor Johnson keeps hearing things. The top of the half-filled kit bag collapses to look like a human face—John Turk’s face! No, no. It’s just the light in here. And Johnson’s a bit on edge. Surely, he hears the landlady, who might have had a bit too much to drink tonight.

Does he see someone on the landing? In any event, that someone disappears.

Johnson is not one to panic, but sumptin’s goin’ on.

The moodiness of the piece is what makes it. Johnson hears and sees things that don’t quite add up. He at first attributes them to the storm and the nerves from the horrendous trial he’s just witnessed. After all, he’s busy packing for a trip—he needs to shake this all off. But wait! What was that?

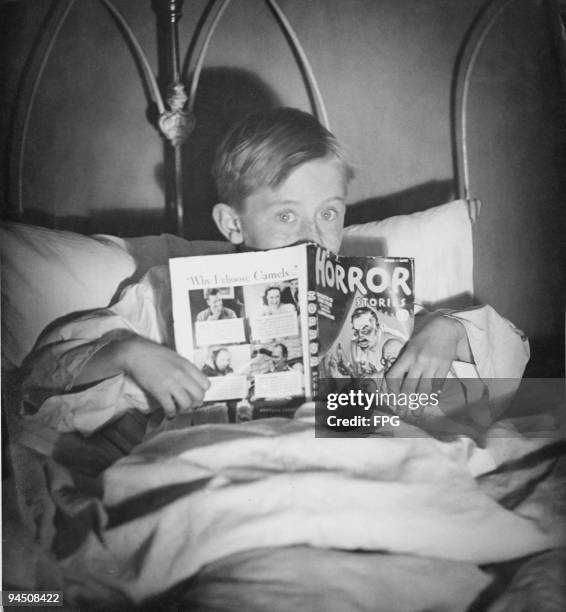

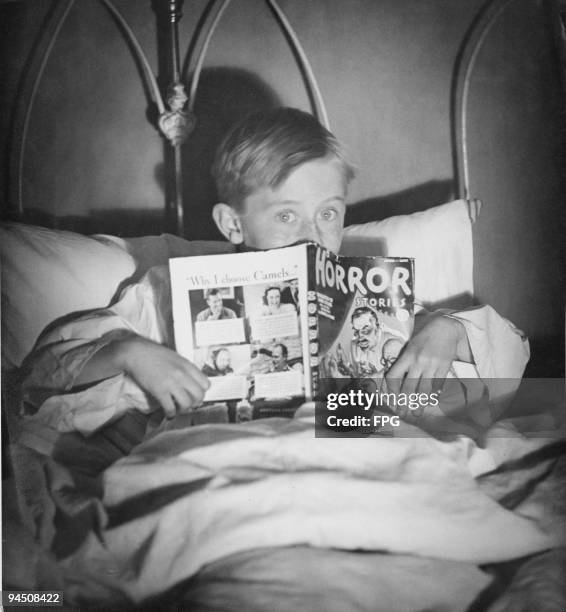

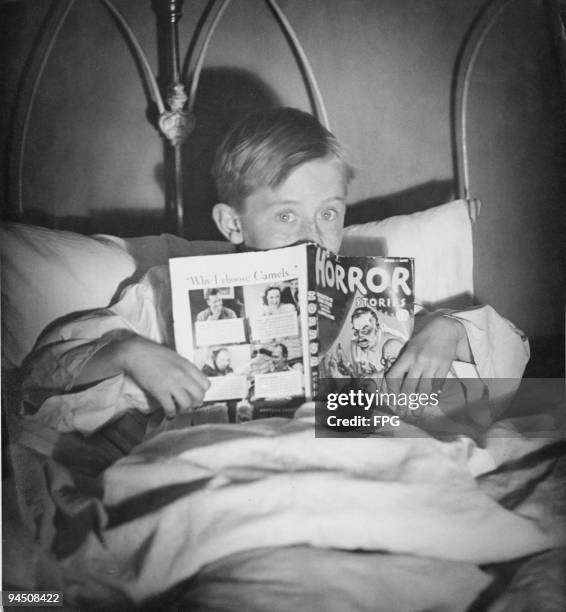

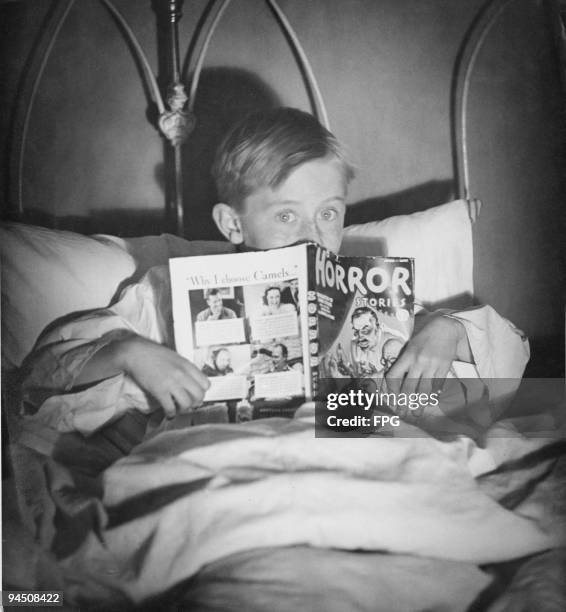

While the ending may be a bit of a letdown, it is also unsettling. This story is one to read late at night, wrapped in a warm blanket and sipping a cup of tea.

Bio: Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951) was a prolific British writer and broadcaster of mystery, horror, and supernatural tales. Before he turned to writing, he spent time in Canada and the US farming, running a hotel, and gold mining in Alaska. He also worked as a newspaper reporter in New York City. He wrote of this time in a memoir, Episodes Before Thirty (1923/1934).

Many of his writings are atmospheric, heavy with unknown or poorly understood menace, such as “The Willows.”

This story can be read here. Thanks, Tracy!

This story can be listened to here: (35:13)

Title: “The Kit-Bag”

Author: Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951)

First published: Pall Mall Magazine, December 1908

Length: short story

Review of “The Haunted Chair” by Richard Marsh: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

As Mr. Philpotts walks into the smoking room of the club, he hears, “Well, that’s the most staggering thing I’ve ever known!” The narrator hints that the actual comment was not quite so tame.

The speaker, Mr. Bloxom, stands in front of his chair, looking around. He asks Mr. Philpotts, “Did you see him?”

“I heard you,” the other replies and points out that Mr. Bloxom’s cigar is on the floor, burning the new carpet the committee has just had installed.

Mr. Bloxom ignores him and demands, “Did Geoff Fleming pass you as you came in?”

This confuses Mr. Philpotts. “Geoff Fleming!–Why, surely he’s in Ceylon [present day Sri Lanka—my note] by now.”

Mr. Bloxom insists he was just in the room. A few moments later, he discovers his wallet is missing. Geoff Fleming, who should be on his way halfway around the world, must have taken it.

Thoughts:

I found it obvious what was happening from the moment poor, flummoxed Mr. Bloxom began looking for someone who was just there—and couldn’t be there. This is a cute little tale. Mr. Bloxom is not the only club member to have a similar adventure and be relieved of something of value.

The members argue with one another. Surely Bloxom, then the next person is losing their marbles. Fleming can’t be here. Even if he were, he couldn’t have gotten out of the room without someone seeing him, right?

This little tale pokes fun at the various club members and the high opinions they have of themselves. Nevertheless, it is sad, demonstrating the lengths one member will go to measure up, at least in his own mind. Yes, he screwed up, but he must keep his word under any circumstances—then all will be forgiven, right?

One drawback is the use of dialect and slang that rely on the particular time and place. For example, when Bloxom realizes his wallet is gone after his brief encounter with Fleming, he complains that Fleming has “boned his purse.”

Bio: Richard Marsh (legal name: Richard Bernard Heldmann) (1857-1915) was a prolific British writer and novelist. His best-known work is the 1897 novel The Beetle. He began writing boys’ fiction. For a brief time, he served as a co-editor at one of the periodicals he’d been publishing regularly in, but then was let go. After serving time for forging checks, he adopted the pseudonym Richard Marsh and began publishing crime, detection, thriller, popular romance, and humor fiction for adults. All told, he published about seventy-six short stories.

This story can be read here:

I could not find an audio version of this story.

Title: “The Haunted Chair”

Author: Richard Marsh (legal name: Richard Bernard Heldmann) (1857-1915)

First published: Between the Dark and the Daylight, April 1902

Length: short story

Review of “A Ghost Story” by Mark Twain: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

The narrator recounts that he took a large room in a huge old building. The upper stories, where his room is, have been unoccupied for years and have long given up to cobwebs, solitude, and silence. He feels he’s invading the privacy of the dead. For the first time in his life, a superstitious dread overcomes him.

He locks the door. While a cheery fire burns, he sits and thinks of bygone times, faces of friends he’ll never see again, voices fallen forever silent, and once familiar songs no one sings anymore. Outside, it begins to rain. He turns in for the night and sleeps profoundly.

He wakes suddenly with the feeling of someone or something tugging the covers toward the foot of the bed. He hears noises of someone walking—no, stomping like an elephant—around the bedroom and the building. He sees disembodied faces floating above the bed…

Thoughts:

While this story begins in traditional gothic ghost story form—the long-unused room, the cobwebs, the rain, the narrator’s ruminations on lost friends and loved ones, and the appearance of the ghost, which terrifies him—it turns on a dime. After all, Mark Twain wrote this tale.

After a second look, he realizes his visitor is a little out of sorts. And stark naked. One can’t be at his best when he’s knocking around a stranger’s room in the middle of the night in the all-in-all.

It ends in farce. Good for Twain. He brings in one of the day’s great hoaxes, the so-called Cardiff (New York) Giant. According to Wikipedia, the Cardiff Giant was created by New York tobacco retailer George Hull after an argument at a Methodist revival meeting about biblical references to giants in the earth. Showman P. T. Barnum then created a replica. It had already been exposed as a hoax when Twain wrote the story.

This is a cute little tale.

Bio: Mark Twain (legal name: Samuel Langhorne Clemens) (1835-1910) was an American writer, novelist, and journalist. He was known primarily as a humorist. As a young man, he worked as a boat captain on the Mississippi River until the Civil War disrupted river trade. He recounted the time in Life on the Mississippi. Among his most well-known books are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), which have lately had their share of controversy.

This story can be read here:

The story can be listened to here: (14:38)

Title: “A Ghost Story”

Author: Mark Twain (legal name: Samuel Langhorne Clemens) (1835-1910)

First published: Mark Twain’s sketches, new and old, 1875

Length: short story

Review of “The Furnished Room” by O. Henry: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

In the turn of the century New York’s Lower West Side, a young man seeks to rent a room. After confirming with the prospective landlady that she rents to a lot of “theatrical people,” he asks if she has recently rented to Miss Eloise Vashner.

“[D]o you remember such a one among your lodgers? She would be singing on the stage, most likely. A fair girl, of medium height and slender, with reddish, gold hair and a dark mole near her left eyebrow.”

The young man has been looking for her for five months.

The landlady denies this.

The young man takes the room, which has the marks of many of its former tenants. As he settles in, the strong, sweet odor of mignonette* fills the room. He cries aloud, “What, dear?” as if she called to him.

He decides that Eloise has been in that room and searches for some token of her. He runs down the hall and asks the landlady about former tenants. She recites a laundry list, none of which sounds like Eloise. When he returns to the room, the scent of mignonette has gone.

Thoughts:

I do wish to warn sensitive readers that the story deals with suicide.

The writing is nicely atmospheric. The young man is never named, but the reader knows the name of the young lady he is searching for. The landlady is quick with useless information, telling him twice that the former lodgers hung their marriage certificate on the wall. They were respectable, after all. So is she—not renting rooms to women of questionable character.

The unnamed young man doesn’t care. He’s looking for his beloved.

The rooms-to-let speak of a transient population, always coming and going. The “theatrical people” are always on the move. Just the same, the places they stay leave traces of their passing, ghosts of their actions, so to speak:

“A splattered stain, raying like the shadow of a bursting bomb, witnessed where a hurled glass or bottle had splintered with its contents against the wall.”

Why shouldn’t the young man expect to find a trace of Eloise there?

The surprise O. Henry ending follows.

This is a sad little tale about a young man who has searched and perhaps found the woman he loves.

Bio: O. Henry (legal name: William Sidney Porter) (1862-1910) was a prolific American short story writer with some 600 short stories to his name. His stories were known for the surprise twist endings. He was born in Greensboro, NC, but settled in New York City. While he was working as a bookkeeper in a bank in Austin, some money went missing. In 1896, on the day before he was to stand trial for embezzlement, he fled to New Orleans and later to Honduras, which had no extradition treaty with the U.S.

He returned on hearing that his wife was gravely ill and was later convicted of embezzlement in 1898, despite some doubts about his guilt. He served three of the five years he was sentenced to, changed his name to O. Henry, and moved to New York City to continue his writing career.

He found success during his lifetime but drank heavily and died of cirrhosis of the liver. He was deeply in debt.

Among his most famous stories are “The Gift of the Magi” (1905) and “The Ransom of Red Chief” (1907).

This story can be read and listened to here: (14:18)

* mignonette 1) a plant, Reseda odorata, common in gardens, having racemes of small, fragrant, greenish-white flowers with prominent orange anthers 2) a grayish green resembling the color of a reseda plant.

Title: “The Furnished Room”

Author: O. Henry (legal name: William Sidney Porter) (1862-1910)

First published: New York Sunday World Magazine, August 14, 1904

Length: short story

Review of “Fishhead” by Irvin S. Cobb: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

“Fishhead” is the unkind name given to the mixed-race main character who lived by swampy Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee. The lake was created by an 1811 series of earthquakes, which caused an area of land to subside and the Mississippi to flood in.

Fishhead’s “half-breed Indian” mother—so the story goes—was frightened by one of the monstrous fish that lived in the lake shortly before Fishhead was born, thus bringing about her offspring’s physical deformities.

He grew up and stayed in a slough by the swampy lake, keeping to himself, “a piece with this setting,” the author tells the reader. “He fitted into it as an acorn fits into its cup.” People told stories about Fishhead: At dusk, some heard a cry “skittering across the darkened waters.” It was Fishhead, calling to the huge, ugly catfish in the lake. They would come, and he’d swim with them and eat with them…

The Baxter brothers, Jake and Joel, come across Fishhead at the skiff landing at Walnut Log one day. Jake and Joel accuse Fishhead of stripping hooked fish off their trot line. They have no evidence of this, but they are drunk. Fishhead answers their accusation in silence. One of them slaps his face. They both receive a fair beatdown for their efforts.

The Baxter brothers find such treatment beneath their dignity and plot revenge.

Thoughts:

The setting of Reelfoot Lake in this short tale is a character in itself. The author takes pains to describe it long before introducing Fishhead, who is part of the land and lake. It sustains those wise enough to understand its ways, but there are also dangers—the skeletons of submerged cypress trees, for example. In some spots, it appears bottomless. In others, it is shallow. And there are always strange creatures and mud—endless mud.

Fishhead’s deformities are not the result of his mixed heritage but the result of the shock his mother experienced shortly before he was born—an old and long-discredited idea. His appearance may be a little hard on the eyes, but he’s well-adapted to his environment and doesn’t bother anyone.

The white Baxter brothers drink, make false accusations, and abuse Fishhead. If their appearance isn’t as ugly as Fishhead’s, their actions are far uglier. They get their collective rear end handed to them—deservedly so—and they can’t accept that a black guy bested them. The story is one of tragedy and unnecessary death brought about by drunk and foolish people who hate without reason someone different from them.

I found this story primarily sad and difficult to read on an emotional level.

Bio: Irvin S. Cobb (1876-1944) was an American journalist, humorist, and author. Originally from Paducah, Kentucky, he began writing at the local paper but settled in New York. He wrote for the Saturday Evening Post (among other papers) and covered Americans serving in France during the Great War, particularly the Harlem Hellfighters. Among his most popular series were the stories of Judge Priest. He also worked in film, both in silent and sound productions. “Fishhead” remains one of his most frequently anthologized stories and served as an inspiration for H. P Lovecraft’s “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.”

This story can be read and listened to here: (29:08)

Title: “Fishhead”

Author: Irvin S. Cobb (1876-1944)

First Published: The Cavalier, January 11, 1913

Length: short story:

Review of “The Familiar” by J. Sheridan Le Fanu: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

This is a case found among the papers of the (fictional) “metaphysical physician” Dr. Martin Hesselius and described by his anonymous assistant.

Sir James Barton has served in the British Navy with distinction for some twenty years, particularly in the American War (American Revolution). In his early 40s now, he returns to Dublin with thoughts of settling down. He becomes engaged to Miss Montague, the niece of a Lady L—. They await the return of Miss Montague’s father from India to formalize things.

One night, on his way home after visiting with Lady L— and Miss Montague, he hears footsteps behind him. It’s late, and the streets are deserted. He looks over his shoulder but sees no one. The footsteps seem to run and stop. The seeming pursuit rattles Barton enough that he calls out. No answer comes.

Barton says nothing to anyone at first, least of all Miss Montague.

Similar incidents follow; Barton hears laughter. One day, he meets a small man in a fur-traveling cap. The man says nothing but looks at him with such vicious malice that Barton’s friends notice he’s taken aback.

Thoughts:

The reader watches Barton’s antagonist circle ever closer. Barton is a materialist and doesn’t believe in the supernatural. These experiences shake his disbelief. He finally seeks counsel from well-intentioned experts—even a clergyman—who tell him in the politest of terms that it’s all in his head. He should get some rest, eat better, and get some exercise.

His questions to a medical doctor reveal that he has something he’d prefer not to remember. It’s not entirely clear to the reader yet. Could lockjaw (tetanus) ever look like death?

The reader feels Barton’s terror and this nameless enemy. Not until the end are an identity and a motive made known, though the reader can make some guesses. The author ratchets up the danger to Barton as the story goes on. The result is not so much righteous anger as sadness.

While things take a while to get going, and the reader has a bit to sit through, I like this sad tale.

Bio: Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873) was an Irish writer of Huguenot descent. His early writings include a group of short stories, initially published anonymously in The Dublin University Magazine in the guise of the literary remains of one (fictional) Father Frances Purcell (The Purcell Papers 1838-1850). These range from the creepy (“Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter”) to the silly (“The Quare Gander”).

Le Fanu’s writings include many ghost stories and supernatural pieces. His works influenced such writers as M. R. James and may have inspired portions of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). His vampire tale, “Carmilla” (1872), influenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula. “Carmilla” has been adapted for film several times with varying degrees of success.

In 1858, his wife died after what was described as a fit of hysteria. Le Fanu ceased writing for years and became a recluse, taking to his bed.

This story can be read here:

This story can be listened to here: (1:30:03)

Title: “The Familiar”

Author: J. Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873)

First published: This is a minor revision of “The Watcher,” first published in the collection In a Glass Darkly (1851). This version was published in 1872.

Length: novelette

Series: Martin Hesselius

Review of “The Entail” by E. T. A. Hoffmann: Halloween Countdown

Plot:

Our hero’s great-uncle V— works as a law agent and “Justitiarius” (other translations call him “Advocate”) for the family of Freiherr (Baron)* R—. Our hero is named V—like his great-uncle. He accompanies the elder V— to the family estates to attend to R— family business.

Uncle V—’s usual rooms are unavailable, having suffered a catastrophic collapse, so Uncle and Nephew are put up in unfamiliar quarters. Nephew dreams of strange, otherworldly things the first night they stay—footsteps when no one is there, sighs and moans, and someone scratching at a sealed-off passage.

In the morning, he relates this to Uncle. Having dreamed these same things, Uncle takes Nephew’s account seriously and banishes the evil presence on the second night. Uncle and Nephew then sleep peacefully.

Nephew despises the baron. Uncle knows why—the baron stands between Nephew and the lovely 19-year-old baroness. Fortunately, the business he and his uncle have is completed before Nephew can do anything really stupid, and they depart.

Sadly, Uncle has a stroke soon after they return home. While recovering and knowing he’s not long for this world, Uncle tells Nephew the story of the family R—. It takes a while.

Thoughts:

This story is long and written without chapter breaks. By my count, the reader will wade through more than 34,000 words, a feat that would be difficult to accomplish in a single sitting.

The R— family history is full of intrigue, murder, betrayal, sleepwalkers (…maybe…), jealousy, a hidden child, and—as the reader learns early—a grandaddy who practiced black magic. Two family members are named Roderick. Two others are named Hubert. Why? Did author Hoffmann run out of given names?

“Entail” was a word not familiar to me. As far as I could puzzle out, it’s a legal term referring to a piece of real estate with limited ownership and inheritance. Old Granddaddy, the dabbler in the black arts, wanted to keep his descendants close, even if his two sons couldn’t stand him. How’d that work out for you, Granddaddy?

The tale wanders. The young narrator, V—, grows older. The elder V— passes away, but not before revealing (at some length) the secrets of the family R—. The horror is real, yet humor appears. Especially when the family history is revealed, things get complicated and a little hard to follow. Mostly, I find the story sad.

I believe the greatest obstacle to the modern reader would be the length of this tale. The next greatest obstacle would be the confusing family history. However, there are rewards for the reader willing to wade through this long story.

Bio: E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776-1822) was a German composer, painter, lawyer, judge, and author. He was born in what was then Königsberg in the Kingdom of Prussia but is now Kaliningrad, Russia. He trained in law, following family tradition. He wrote more than fifty stories—not all of which have been translated into English—musical compositions like the opera Undine, one complete novel, The Devil’s Elixir (Die Elixiere des Teufels), and an incomplete novel, The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr (Lebens-Ansichten des Kater Murr). One of his stories, “Nutcracker and Mouse-King” (“Nußknacker und Mausekönig”), inspired Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker. His most well-known story is probably “The Sandman,” which is not related to the Neil Gaiman series of the same name.

Most of Hoffman’s works deal with the supernatural or uncanny, whether ghosts, automatons, or doppelgangers. His writings influenced writers as diverse as Alexandre Dumas, Nikolai Gogol, Franz Kafka, Leo Perutz, and Edgar Allan Poe.

*The meaning of the titles changed a bit over time, but “baron” is close enough for jazz.

This story can be read here:

This story can be listened to here: (in ten sections: total time approx. 3 & half hours)

Title: “The Entail”

Author: E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776-1822)

First published: 1885 in English; originally “Das Majorat” [German] (1817)

Length: novella

Review of “The Dreams in the Witch House” by H. P. Lovecraft: Halloween Countdown

Walter Gilman, a student at (fictional) Miskatonic University in (fictional) Arkham, Massachusetts, deliberately rented the tower room in the old house where accused witch Keziah Mason disappeared in 1692. His fields of study include “non-Euclidean calculus and quantum physics.” He also has an interest in folklore, all of which leads him to trace multidimensional space.

The room is oddly portioned; the ceiling slants to meet a wall that tilts inward. There may be an attic above his room, but the landlord says it’s been sealed off for ages and won’t hear talk of exploring what might or might not be there. The locals talk of an indescribable creature that darts rat-like around town. They’ve named it Brown Jenkin.

When Keziah Mason disappeared from the same room where Gilman sleeps and studies, “the jailer had gone mad and babbled of a small white-fanged furry thing which scuttled out of Keziah’s cell, and not even Cotton Mather could explain the curves and angles smeared on the grey stone walls with some red, sticky fluid.”

Gilman dreams. He sees shadows, which eventually resolve into a bent old woman and a rat-like creature with a human face and beard. He begins to sleepwalk, even discovering mud on his feet in the morning. Are his dreams really dreams? Or is he going somewhere?

A child goes missing from one of the poor families in town. Her mother says she’s not surprised; Brown Jenkin has been spotted, and everyone knows Walpurgisnacht, the night of the witches’ Sabbat, is approaching.

Thoughts:

I have to warn any potential readers that this story is gory and deals with the deaths of children.

Perhaps because it mentions the Elder Things, Nyarlathotep, The Necronomicon, The Book of Eibon, and Unaussprechlichen Kulten*, the story is associated with the Cthulhu Mythos.

Poor Gilman sees a connection between modern knowledge of mathematics and science and the knowledge of the old wise women. Somehow, Keziah learned to travel in extra-dimensional space that modern science is just now finding out about.

At one point, the reader is told, “Possibly, Gilman ought not to have studied so hard.” He found the records of Keziah’s trial fascinating. She admitted to the judge at the Court of Oyer and Terminer that one could use lines and curves to point out directions leading through the walls of space to other spaces beyond and implied that such lines and curves “were frequently used at certain midnight meetings.”

This was Judge John Hathorne, a historical person and an ancestor of the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Much of the action is in dreams that say more than the words. Why doesn’t Gilman leave? When he starts sleepwalking, why doesn’t he take measures against it? The dreams terrify and confuse him. But they’re only dreams, right? Gilman isn’t evil. He’s merely curious. The things that happen to him do so because he dares to look in places others are too afraid (or too wise) to do so.

This tale is sad and gory. It poses an intriguing question; those with the wits and the will to ask questions suffer for their efforts.

Bio: H.P. (Howard Phillips) Lovecraft (1890-1937) was an American writer of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. He is best known as the creator of the Cthulhu myths, which involve “cosmic horror,” that is, a horror that arises from the dangers that surround us mortals, but remain so far from our everyday lives that we don’t and can’t see them. Those who seek knowledge of it are often driven insane or die.

Lovecraft originally wanted to be a professional astronomer. He maintained a voluminous correspondence, particularly with other writers. Though his work is now revered as seminal in horror and dark fantasy, he died in poverty at the age of 46 of cancer of the small intestine at his birthplace, Providence, Rhode Island.

Lovecraft was an early contributor to Weird Tales magazine in the 1920s. Among his best-known works are “The Dunwich Horror,” “Dagon,” and “The Call of Cthulhu.”

This story can be read here:

This story can be listened to here: (1:37:50)

*The Elder Things are fictional aliens. Nyarlathotep is a vicious deity, often seen as the messenger of Azathoth, the ruler of the Outer Gods. The Necronomicon is the fictional grimoire of Lovecraft. The Book of Eibon is a fictional book of Clark Ashton Smith’s, having to do with a wizard’s journeys and magic. Unaussprechlichen Kulten (Unspoken Cults) is a fictional book by Robert E. Howard. These are all part of the Cthulhu Mythos.

Title: “The Dreams in the Witch House”

Author: H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937)

First published: Weird Tales, July 1933

Length: novelette

Series: Cthulhu Mythos (Lovecraft originals)