Our latest Saturday pizza and bad movie offering was something of a departure. Though it’s called “supernatural horror,” this flick at first brought to mind 70s disaster movies like Airport.

Plot:

Vista Pacific Airlines flight 7500 departs from Los Angeles to Tokyo Haneda. Lyn (Aja Evans) and Jack Hafey (Ben Sharples) are vacationing with their friends, and Brad (Ryan Kwanten) and Pia Martin (Amy Smart), who have recently broken up. They didn’t want to tell their friends because they’ve already paid for the trip for them.

A young man with dark hair named Jake (Alex Frost) tries to sell a hot phone to a young woman named Raquel Mendoza (Christian Serratos). Raquel declines the offer and keeps on working on her sketches.

A businessman, Lance Morrell (Rick Kelly), traveling with a strange wooden box, makes the viewer wonder: Is that a bomb? Is he transporting stolen money? Drugs? Hmmm…

Newlywed Rick (Jerry Ferrara) gets to watch his bride, Liz (Nicky Whelan), go through their wedding pics one more time—again. Liz likes to wipe down the seat handles, especially after a young goth girl, Jacinta Bloch (Scout Taylor-Compton), sits down next to her.

In the galley, flight attendants Laura Baxter (Leslie Bibb) and Suzy Lee (Jamie Chung) talk about Suzy’s engagement and Laura’s affair with the married Captain Pete Haining (Johnathon Schaech).

The plane takes off (no snowstorm in sight), and all seems well until they hit a bit of turbulence. It’s over quickly, except for Lance, who appears to be in some sort of cardiac distress. Brad, a paramedic, tries to help him. Lance can’t breathe. Blood drips from his lips. Despite Brad’s best efforts, Lance seizes and dies.

Captain Pete decides not to turn the plane around, but to continue. (Wouldn’t you want to land as soon as possible, especially if Lance’s death was possibly caused by disease and not a heart attack?) He clears out the first-class section (upstairs) and has the passengers brought downstairs with promises of vouchers for later flights. As the late Lance Morrow is carried by, the goth Jacinta seems intrigued. She later tells the newlywed Rick, “Death is part of life.”

Back in his seat, Brad notices his thumb turning black, a sign of hypoxia. His sealed water bottle is compressing, another bad sign. (I’m given to believe that a sealed water bottle would actually expand during rapid decompression. Details.)

Uh-oh. It looks like some good stuff is about to hit the fan.

Thoughts:

After poor Lance shuffles off his mortal coil, the four vacationing friends become Scooby and the Gang and begin looking for clues about him. By going through his wooden box, they turn up some creepy and puzzling stuff about him. Flight attendant Laura also goes sleuthing, including dropping down into the baggage compartment. Was someone down there?

These elements struck me as incredibly unlikely. They also don’t make a whole lot of sense. Is this a dream sequence? Is it real? Or is something else happening?

Adding to the feeling of unreality, or perhaps irrationality, are events like the moment when one passenger is viewing something on his phone, and scenes from the old Twilight Zone episode (“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”) showing William Shatner watching a gremlin tear up a wing of an airplane flash on his screen.

The plight of the passengers resembles a real-life tragedy from some years ago, which, to discuss further, would spoil some plot points. This also adds to the feeling of reality v. illusion. What’s going on here?

At one point, I turned to the dearly beloved and said something to the effect of, “Huh?”

An explanation arises, and it’s not quite what the view has been led to think. Part of me wants to say this could have been a moving and poignant story, even with the creepy horror. Another part of me says some of the events served as mere distractions that detracted from the story. I liked what it was trying to convey, however. I’m on the fence about this one.

I could not find a place to download it for free, but YouTube will rent it or sell it to you.

Title: Flight 7500 (2014)

Director

Takashi Shimizu

Writer

Craig Rosenberg

written by

Cast

(in credits order)

Ryan Kwanten…Brad Martin

Amy Smart…Pia Martin

Leslie Bibb…Laura Baxter

Jamie Chung…Suzy Lee

Scout Taylor-Compton…Jacinta Bloch

Released: 2014

Length: 1 hour, 20 minutes

Rated: PG-13

Review of “The Skull” (1965)

We’ve kept up our pizza and bad movie nights, but I’ve slacked off on reviewing the various gems. But by special request, I’ll add at least one more.

Remember—you asked! 😊

Plot:

In an early 19th-century graveyard, cloaked men carrying lanterns and shovels make their way toward a specific grave. At certain points, the trees sway in the wind. At others, a wrought iron gate slams in the wind, and the trees stand still. The men put shovel to earth.

While they’re working, the credits roll across the screen, telling the viewer that the movie is based on the short story “The Skull of the Marquis de Sade” by Robert Bloch (who also wrote Psycho). Well, guess who they’re looking for.

One of the men, Pierre (Maurice Good), a phrenologist, returns to his lab with his prize in a cloth bag. To his surprise, his lady friend (April Olrich) is waiting for him. Not now, when he’s got important things to do! She retires to the bedroom to munch on bonbons or marshmallows or something.

The phrenologist pours a mixture of chemicals into a sink. Smoke rises, obscuring nearly everything. (Pierre neglects to don an apron or goggles. Didn’t get the OSHA bulletin, I guess.) He’s going to deflesh the skull.

The lady friend puts down a marshmallow to see smoke pouring out from under the door of her beloved’s lab. She rushes in—and screams.

Oh, if that were the only unhappy thing she experiences.

In the mid-20th century, Christopher Maitland (Peter Cushing) and Sir Matthew Phillips (Christopher Lee), two collectors of occult items, sit at an auction of oddball items. With Maitland is Anthony Marco (Patrick Wymark), a dealer advising him on various offerings.

Four statues of demons come up. Maitland wishes them for his “studies,” but Phillips outbids him. He seems compelled to buy them.

Marco later shows up at Maitland’s home. Mrs. Maitland (Jill Bennett) doesn’t like him. She thinks he’s creepy. Can’t imagine why.

In the privacy of Maitland’s study, Marco offers Maitland a biography of the Marquis de Sade for a cool £ 200 when he tells him the cover is made of human skin. ICK.

He promises to bring something even more intriguing.

Later, when Maitland and Phillips are discussing the promised skull over a game of pool, Maitland expresses understandable skepticism about the artifact’s authenticity.

“Oh, it’s real,” Phillips tells him. “Marco stole it from me.” He also warns Maitland to stay away from the skull because it’s dangerous.

Yeah, like that would keep his friend away.

Thoughts:

This flick is full of moody, atmospheric sets and music. Occult art objects overrun Maitland’s study. One dream sequence in particular brings to mind Alice in Wonderland and the old British TV show, The Prisoner. The film’s POV at times is through the skull and tinted green or other odd colors. The skull never speaks or laughs. It occasionally flies. Mostly, it sits and menaces.

While Maitland wrestles with his newly induced murderous urges, his wife sleeps peacefully. Maitland pounds on the locked doors of his study, screaming for help, and she stirs in her slumber. The skull forces him into her bedroom. He holds a knife over her, ready to plunge it into his unsuspecting beloved wife. She turns over, displaying the cross at her neck.

Thwarted, as if he were a vampire!

And his wife never wakes.

He’s having a terrible day. She’s having a long nap.

The movie deals next to not at all with the historical person of the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) or his writings, which is just as well. It could almost as easily have used some anonymous dabbler in black magic. Frankly, I was concerned it might glorify that violent and disturbed person, but it did not.

As for recommending it, I am on the fence. I had a great time with its silliness, and I enjoyed the intricate sets, off-kilter camera angles, and the surrealism. The special effects were unconvincing, but that never bothers me. I don’t mind seeing the strings.

I could not find a place to download this fine flick.

Title: The Skull (1965)

Director:

Freddie Francis

Writers:

Robert Bloch from the story “The Skull of the Marquis de Sade” by

Milton Subotsky screenplay by

Cast:

(in credits order) verified

Peter Cushing…Christopher Maitland

Patrick Wymark…Anthony Marco

Christopher Lee…Sir Matthew Phillips

Jill Bennett…Jane Maitland

Nigel Green…Inspector Wilson

Released: 1965

Length: 1 hour, 23 minutes

Rated: Approved

A Few Thoughts…

Oddly, a review I wrote for Goodreads in 2012 popped up on my radar. I excoriated a piece of anti-abortion propaganda disguised as a YA romance book. I can’t remember what induced me to read it in the first place—perhaps I lost a bet?

I was all prepared to unleash a new and improved rant and went looking for bio info on the author. Certainly, she’d been up to something besides writing a (*shudder*) sequel.

The author seems to have been inactive for several years, but I found her Facebook page. She’s suffered several personal losses recently, including her husband and her father. There were no references to her writing. A couple of posts talked about COVID.

I turned things over in my mind. She would almost certainly never see my review. Whether she saw the original Goodreads review, I have no way of knowing. What is the point of reposting such a negative review of her book now, when so few impressionable young people are in danger of buying it? I can’t imagine it was a huge seller even when it was first available. The sequel doesn’t even show up on Amazon.

Posting the review will not warn anyone off from buying the book who might otherwise have stumbled across it. There are many fine YA novels out there, enjoyable for all ages. This didn’t happen to be one of them.

So, while I had a lot of fun tearing up the little book, I will let it go.

Now, on to the, you know, revolution—or dinner. Whichever one comes first.

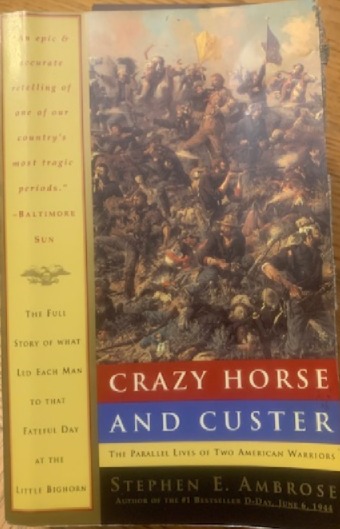

Review of “Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors” by Stephen E. Ambrose

A word upfront: when I bought this book at a used bookstore and started reading it, I was unaware of allegations of plagiarism, fabrication, and misstatements of fact made against this author. Some of the oopsies include the following book, so I can’t in good conscience recommend it, even if it were a fantastic read.

I was also unaware that the author, writing in the 1970s, was such a proponent of Manifest Destiny (p. 323, see below), something that (caveat lector) provoked a bit of ranting and raving on my part. Out of habit, however, I have to give my opinion on the reading experience, just cuz.

The Stuff:

The subtitle names Crazy Horse, a 19th-century Oglala Sioux, as an American warrior. Without speaking for him, I can’t help wondering if he might find this designation a surprise, to say the least.

In his introduction, Ambrose points out that while both men had many things in common, they were also quite different. Crazy Horse was born around 1840, and George Armstrong Custer in 1839. Custer died in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which has come to be known as Custer’s Last Stand. Crazy Horse died in 1877. Both men won honors and were considered leaders; both were involved in career-endangering scandals.

The author promises the reader a story of how Custer and Crazy Horse found themselves at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Ambrose recounts what is known of both men from birth through childhood, into adolescence, and manhood. He describes their careers and the societies they grew up in.

Each chapter opens with an unsigned line drawing. I could not find the artist’s name. If it was Ambrose himself, how modest of him.

Thoughts:

Ambrose is a storyteller in the best sense of the word. He recounts an 1854 incident involving Second Lieutenant John L. Grattan, who died with the rest of his detachment trying to arrest Miniconjou High Forehead for the alleged theft of a Mormon immigrant’s cow. Grattan was twenty-four years old and “fresh out of West Point.” He had never seen the Sioux in battle, “was certain that such an ill-organized, undisciplined bunch of savages could never stand up to a force of U.S. Infantry.” (pp. 60-61 ff)

He went in with thirty men and a howitzer. There were some negotiations, but High Forehead refused to surrender, and no one was going to compel him. Amid some complications (a drunken interpreter, whom the Sioux hated, provoking and jeering at the Indians, for one), someone shot first. Grattan and his thirty men all died and were mutilated by the Sioux. The lesson Ambrose is trying to depict is that inexperienced white men who underestimate the capabilities of the Indians, overestimate their own, rush into battle, and will die.

This tragedy foreshadows Custer’s death and disaster at the Little Bighorn.

Ambrose portrays both men as living and dying violently. The reader sees Custer as charming, playful, cheerful, but irresponsible. He is fearless in battle, but also careless with the lives of the men he leads. An indication of this is his claim to have had fifteen horses shot out from under him over time. Well, can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs, I guess. He would be the ultimate happy frat boy in current times, perhaps.

Crazy Horse, by contrast, was solemn and silent. He is violent but does not take the lives of the men with him for granted. His dream vision told him dress modestly and not to keep anything he won in battle for himself, but to take his responsibility to the defenseless. He was known as a great hunter in addition to being a warrior.

Of the two, Custer comes off as the jerk. He’s impetuous, and Crazy Horse is the more thoughtful and measured.

*WARNING: RANT TO FOLLOW*

Ambrose discusses not only the Grattan Massacre, but also the 1868 massacre of a Cheyenne winter camp led by Custer that killed perhaps 100 indigenous people, including the peacemaker, Black Kettle. He details the destruction of the village, the food stores, and, aside from ponies for the captives, the destruction of the herd of some nine hundred ponies. The author notes that, as a horse lover, killing so many healthy animals probably bothered Custer.

Unlike killing the healthy humans? The women and children…?

Pretty bleak. He doesn’t excuse Custer, but later, he says, you know, right and wrong are sort of malleable concepts, aren’t they?

“Well, [the destruction of such a ‘noble and romantic people’ as the indigenous] was regrettable, but who is to say [the expansionist Americans] were wrong? Who would be willing to tell the European immigrant that he can’t go to the Montana mines or to the Kansas prairie because the Indians need the land, so he had best go back to Prague or Dublin? Who wants to tell a hungry world that the United States cannot export wheat because the Cheyenne hold half of Kansas, the Sioux hold the Dakotas, and so on? Despite the hundreds of books by Indian lovers denouncing the government and making whites ashamed of their ancestors, and despite the equally prolific literary efforts on the part of the defenders of the Army, here if anywhere is a case where it is impossible to tell right from wrong.

“But we can tell truth from falsehood. It is, for example, totally irresponsible to state—as has so often been stated—that the United States pursued a policy of genocide toward Indians. …The United States did not follow a policy of genocide; it did try to find a just solution to the Indian problem. The consistent idea was to civilize the Indians.”

(p. 323)

… really, dude? You can’t tell if it was right or wrong to slaughter people and destroy their way of life so other people could control their land? Did you flush your moral compass down the crapper?

And how kind of the United States to “civilize” people at the point ot gun. He even admitted there were deliberate efforts to eliminate the buffalo so the “free Indians” would have nothing to hunt to sustain themselves. I believe Ambrose passed away before the abuses of the Indian boarding schools in the U.S and Canada came to light, but really, did those horrors surprise anyone?

And get the boy a dictionary—large print—so he knows genocide when he sees it.

*END MOST OF RANT*

Bottom line, no. I do not recommend this book for anything other than maybe skeet shooting. If the plagiarism accusations are accurate, it is sad that the author did not do his own homework and give proper credit. But his support for Manifest Destiny is fatal. So, avoid this book like the plague.

I generally give away most books once I’m done reading them, unless I intend to reread them or keep them for reference purposes. This one, however, I can’t let loose on an unsuspecting world. It stays in the darkest corner of the bookshelf.

Bio: Stephen E. Ambrose (1936-2002) was an American historian, writer, and academic. Most of his works concentrate on the Second World War. He also wrote biographies of Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. Among his most notable works are Band of Brothers (1992), D-Day (1994), Undaunted Courage (1996), and Citizen Soldiers (1997). In 2002, allegations arose that he’d plagiarized some of his works. Those charges and apparent misstatements of fact have cast a pall over his writing, sadly.

Title: Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors

Author: Stephen E. Ambrose (1936-2002)

First published: January 1, 1975

Length: nonfiction book

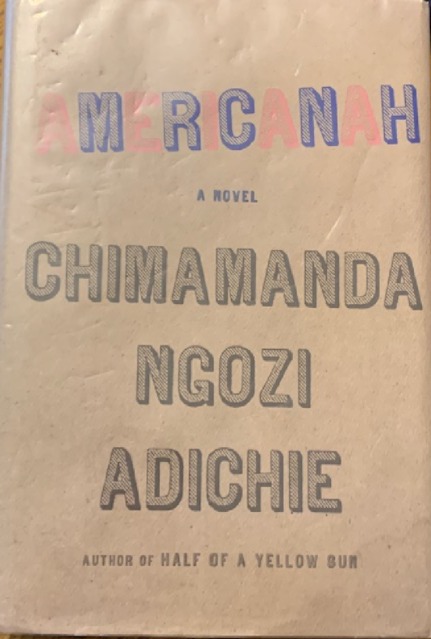

Review of “Americanah” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Plot:

This book is more of a character study than a narrative with a plot. Ifemelu is a young Nigerian woman who comes to the United States for a postgraduate education. The book begins as she is about to return to Nigeria and stops in a hair salon to have her hair braided. This is meaningful. One piece of advice she received upon arriving in the U.S. was that ditching her braids and straightening her hair would help her get a job.

In the meantime, the reader hears about her departure from Nigeria, her religious mother, and her bookish father. There is also her boyfriend, Obinze, back in Nigeria, who loves everything about America but cannot get a visa because of restrictions after the 9-11 attacks. For a while, he lives in Great Britain without papers.

Ifemelu writes a blog titled “Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black.” To her amazement, it becomes popular and lucrative enough to pay the bills. Her observations are sometimes amusing but often angry. They are accurate. For example, she became “black” when she moved to America without changing. Another observation is noting skinny white people at one train station and fat black people at the next. “Fat” in America is pejorative. In Africa, it’s simply a fact. One of her regrets about leaving the U.S. for Nigeria is closing the blog.

While Ifemelu is getting her hair braided, the reader learns about her time in the United States. The reader also learns about Obinze’s fortunes. After his deportation from the U.K. to Nigeria, he prospers. He marries and has a daughter.

Thoughts:

In one respect, the book reads like an extended version of Ifemelu’s blog. It is observations with some commentary. It is almost picaresque as Ifemulu moves through her adventures in America over the course of some fifteen years. A whole host of characters come and go. What does Ifemelu want? That’s a little hard to tease out, for she seems dissatisfied with everything and everybody. She’s embarrassed when her parents come to visit from Nigeria.

The term “Americanah” is a Nigerian term for a Nigerian who has newly returned to the home country after a stint in the United States.

Coming from a family with immigrants myself, I related to the immigrant stories. In America, a party means people sit around, talk, and drink, Ifemelu finds out. That there is no dancing is a disappointment.

Shortly after arriving in the U.S., Ifemelu stays with her Aunt Uju. She notices differences in her aunt’s behavior. She now pronounces her name “you-joo” instead of “oo-joo” because that’s what Americans call her. In the grocery store, Uju’s small son Dike grabs a cereal box after Uju has forbidden it:

“Hi, little guy!” The cashier was large and cheerful, her cheeks reddened and peeling from sunburn. “Helping Mummy out?”

“Dike put it back,” Aunty Uju said, with the nasal, sliding accent she put on when she spoke to white Americans, in the presence of white Americans, in the hearing of white Americans. Pooh-reet-back. And with the accent emerged a new persona, apologetic and self-abasing. (p. 109)

Dike gets his cereal, but in the car, he also has his ear grabbed and is threatened with a slap “before he can hear.” Aunty Uju complains about how spoiled kids are in this country.

Igbo language phrases appear untranslated throughout. Most can be understood in context. A common one is “ahn-ahn,” said when someone is surprised by or disagrees with something, often something said by another person:

“Ifem, [what?]” Aunty Uju asked. “I thought you would be in Nsukka. I just called Obinze’s house.”

“We’re on strike.”

“Ahn-ahn! The strike hasn’t ended?”

“No, that last one ended, we went back to school, and they started another one.”

(p. 100)

Google Translate renders “ahn” as “oh,” but there’s obviously a bit more behind the word.

I’ve read glowing reviews of this book, some of which make it sound like the best thing since sliced bread, which is one reason I read it. There are a lot of enjoyable elements to it. With humor, satire, and engaging and relatable parts, this work had a lot to recommend it. I chuckled while reading. I found the story to be more episodic than a plot, but it is enjoyable and insightful, so it depends on what the reader is expecting.

Bio: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (b. 1977) was born in Nigeria of Igbo parents. She holds a B.A. in political science from Eastern Connecticut State University, a Master’s in creative writing from Johns Hopkins University, and studied African history at Yale University. Her other books include Half a Yellow Sun, which deals with the Nigeria-Biafra War (1967-1970). Her writing often includes themes of anti-racism and feminism. She is regarded as one of the leading African writers.

Title: Americanah

Author: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (b. 1977)

First published: 2013

Length: novel

Review of “The Shadow of the Wind” by Carlos Ruiz Zafón

Plot:

In 1945, Barcelona, Spain, Daniel Sampere’s father, a bookseller, allows him to choose one book from the Cemetery of Forgotten Books. The father does this to comfort him after Daniel realizes he can no longer remember what his late mother looked like.

He chooses The Shadow of the Wind by Barcelona author Julián Carax, an exceedingly rare book. Not even Daniel’s father has heard of the author.

They consult a colleague of Mr. Sempere, Gustavo Barceló. He tells Daniel that very little is known about Carax. His books have become quite valuable because they are so hard to find. Mr. Barceló offers to buy the book, but Daniel declines. However, he develops a crush on Mr. Barceló’s niece, Clara, who is blind. Mr. Barceló invites him to come by and read the book to Clara, which he readily agrees to, despite Clara being several years older than he is.

Some years later, Daniel invites Clara to his sixteenth birthday party. She doesn’t come. Despondent, he wanders the streets and meets a stranger without a face. The stranger introduces himself as Lain Coubert, the name of a character in Carax’s book, and offers to buy The Shadow of the Wind from Daniel. The stranger is destroying all copies of the book. Daniel declines and races to the Barceló house, where the book is, afraid the stranger may hurt Clara. He discovers the reason why she didn’t come to his party and finds himself no longer in love with her.

He begins a search for Julián Carax, a twisting journey that brings in several other people. In the meantime, he falls in love, meets a mentor, uncovers secrets, and watches a friend with a political past run afoul of the police.

Thoughts:

Most commentators and reviewers refer to this book as a mystery, and it is that. Daniel wants to uncover what happened to the author Julián Carax. His search leads him to people who lie to him, to people who were abandoned, and to the deserted estate of the wealthy Aldaya family, where he discovers a tragedy related to Carax.

The story is engaging and sad, but where the book excels is in painting settings and mood. For example:

My throat was burning with cold when, panting after the run, I reached the building where the Aguilars lived. The snow was beginning to settle. I had the good fortune of finding Don Saturno Molledea stationed at the entrance. Don Saturno was the caretaker of the building and (from what Bea had told me) a secret surrealist poet. He had come out ot watch the spectacle of the snow, broom in hand, wrapped in at least three scarves and wearing commando boots.

“It’s God’s dandruff,” he said, marveling, offering the snow a preview of his unpublished verse.

The magical realism and Gothic elements are integral to the story and the characters rather than mere ornaments. The reader is invested in Daniel from the beginning. He can be careless and a jerk at times, but never is he malicious. When he falls in love with the wrong woman, the reader knows it will end painfully.

While the book is long and complicated because of the sheer number of characters, I found it enjoyable for its dreamlike atmosphere. I liked it.

Bio: Carlos Ruiz Zafón (1964-2020) was born in Spain and wrote some young adult fiction. He also wrote screenplays and worked for advertising agencies. He moved to Los Angeles in 1994. His The Shadow of the Wind brought him global fame. It was the first in The Cemetery of Forgotten Books series.

Title: The Shadow of the Wind (original: La sombra del Viento)

Author: Carlos Ruiz Zafón (1964-2020)

First published: 2001, Spain

Translation: 2004, Lucia Graves

Length: novel

Series: Cemetery of Forgotten Books #1

Review of “Family Lore” by Elizabeth Acevedo

Plot:

Widowed and about 70, Flor Marte asks her family for a living wake so she can enjoy it while she’s still here. She’ll get to see everyone again, especially her three sisters, Matilde, Pastora, and Camila. They are originally from the countryside of the Dominican Republic and immigrated to the United States at different times.

Each woman was born with a gift. Flor predicts death. She dreams her teeth are smashed. Pastora can tell if someone is telling the truth. Ona, Flor’s anthropologist daughter, has an “alpha vagina.”

When Flor asks for the living wake, everyone wonders if she is well. Has she had a dream? She says very little. She asks for this favor.

The action of the book starts six weeks before Flor’s wake, with most of it concentrated in the few days before. However, flashbacks tell the stories of the sisters and their daughters.

For example, the reader learns of the courtship and wedding of Mati and her wandering husband. His constant philandering leads to consequences that reach into the present, forcing Mati to make a choice she’s been avoiding for decades.

Thoughts:

The anthropologist Ona, interviewing family members for a project, provides the framework for the book. A couple of short chapters appear in question-and-answer form. In more places, comments from Ona occur as insets, like notes. The narrative moves back and forth between the past and the present.

This sounds more complicated than it is. What emerges is a mosaic of an immigrant family story, remembering the home country while living in the new one.

Author Acevedo provides a list of characters at the beginning of the book, with descriptions of how they’re related and their supernatural gifts. This is helpful but also shows how many characters the reader has to contend with. I had to refer to the list more than once (“Whose daughter is Yadi again?”)

There is a bit of untranslated Spanish throughout the book. I was proud of myself when I read a complete sentence and understood it. Most of the meanings are clear from context, however. I can understand where other English speakers might find this a bit distracting, however.

I liked the characters and cared what happened to them. I enjoyed the stories of their lives, even if the men, for the most part, got short shrift. Many are philanderers or predators. In general, they are useless.

The ending is not a surprise. The reader knows about Flor’s dream early in the book, though she tells no one. There is acceptance and peace rather than mourning, but she wants to go on her terms.

Family Lore was shortlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel 2023 Prize and longlisted for the NAACP 2024 Image Awards. Just the same, many of the reviews I read online complained about the large cast of characters. It does take a little effort, but I enjoyed reading about the characters—their squabbles, triumphs, and losses—so I found the effort worth it.

There is humor and enjoyment of life. For example, Matilde takes dance classes. Why shouldn’t she? She likes to dance, even if she isn’t sixteen years old anymore.

While I can understand this book isn’t for everyone, I enjoyed it and found it easy to read, stumbling over the Spanish notwithstanding.

Bio: Elizabeth Acevedo was born in Harlem to Dominican immigrant parents. She is best known for her YA books and poetry. Her debut novel, The Poet X (2018), was a New York Times best seller and won a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Family Lore is her first novel for an adult audience.

Title: Family Lore

Author: Elizabeth Acevedo

First published: 2023

Review of “What You Are Looking For is In the Library” by Michiko Aoyama

Plot:

This is a collection of five interrelated stories of people who come into the library in Hatori Community House in Tokyo. There, the librarian asks each person, “What are you looking for?”

Ms. Sayuri Komachi, the librarian, is not a mousy person with black-framed winged glasses, but something of a presence. In the first story, twenty-one-year-old Tomoko is looking for books on Excel, which she wishes to learn to help her find a better job. She describes Ms. Komachi:

“My eyes nearly jump out of their sockets. The librarian is huge…I mean, like really huge. But huge as in big, not fat. She takes up the entire space between the L-shaped counter and the partition. Her skin is super pale—you can’t even see where her chin ends and her neck begins—and she is wearing a beige apron over an off-white loose-knit cardigan. She reminds me of a polar bear curled up in a cave for winter.” (p. 25)

Ms. Komachi asks her not only what she is looking for, but why she wants it. She then types on the keyboard, tatatatat, and produces several books that seem relevant to Tomoko’s request and one that does not. She also gives her a “bonus gift,” a little frying she’s made of felt.

Tomoko finds the oddball book the most useful, not in helping her find another job, but in making her happy.

The same pattern repeats in different forms in the other stories; Ryo, a thirty-five-year-old who works in the accounts department of a furniture manufacturer and dreams of opening an antiques store; Natsumi, a forty-year-old, former magazine editor who finds herself marginalized when she returns to work after having a child; Hiroya, a thirty-year-old NEET (not in employment, education or training) who once dreamed of being an artist; and Masao, who at sixty-five, is having a hard time adjusting to retirement.

Thoughts:

The loaded question, “What are you looking for?” has to do with more than just books. Each person who comes to the library is also trying to improve their life. Some are at a crossroads. The librarian is magic (or is she?). She looks and acts oddly. She asks intrusive questions, but the interrogatee does not resent this. On the contrary, they feel warmth and comfort in her presence. But they understand when the interview is over.

She is depicted with a hair bun, spiked by hairpins, from which three white flower tassels hang, a traditional Japanese hairstyle. Maybe there’s something in Japanese folklore I’m not picking up on, but my guess is Ms. Komachi is not entirely human.

Many who have reviewed this book note that it is inspirational and offers hope. While I don’t wish to detract from that, I also sensed an underlying theme. Most of the stories dealt with employment. The book opens with Tomoko, who is beginning her career, and ends with Masao, who has retired. Happiness generally comes from being a productive member of society.

Some of the off-topic books the librarian recommends seem to come out of left field: children’s books, books on worms (useful for gardeners?), or books of poetry. They are real books, listed along with other books mentioned in an index at the back. Perhaps of limited use to the non-Japanese-speaking reading public, but these are interesting all the same.

The similarities in the stories did not make them boring or tiresome. The characters are individual and well-drawn. They face different situations with unique outcomes.

I did not get the feelings of hope and inspiration that others who have reviewed the book have written about. Not that the book offered defeat, despair, and gloom, either. The reading remained interesting, despite the repetition, and the character of the librarian was herself intriguing. This was a fairly quick read.

I enjoyed it.

Bio: Michiko Aoyama (b. 1970) is from Honshu, Japan. She has been a reporter for a Japanese newspaper based in Sydney and worked as a magazine editor in Tokyo. The author’s debut novel is Hot Chocolate on Thursday. Its companion novel is Matcha on Monday. What You are Looking for is in the Library was shortlisted for the Japan Booksellers’ Award, in addition to being a Time Book of the Year, a Times bestseller, and a New York Times Book of the Month.

Title: What You Are Looking For is in the Library

Author: Michiko Aoyama (b. 1970)

Translated by: Alison Watts

First published: 2023

Length: 300 pages

Review of: “The Right of the People: Democracy and the Case for a New American Founding” by Osita Nwanevu

Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.…

Winston Churchill, 1947

The Stuff:

This book is an examination of American democracy, in theory and practice. It offers a variety of prescriptions to aid that ailing democracy, some of which are easier to administer than others. Ancient Athens may be the birthplace of Western democracy, but its current practice bears little resemblance to that of the ancients.

Author Nwanevu states that democracy offers us three valuable tools for governance: agency, dynamism, and procedure. Democracies can be designed and implemented in different ways, depending on need, balancing participation, representation, and deliberation.

That sounds rather abstract, but the author defines each term and takes the reader through a mini-essay on each. It’s still abstract, but coming into focus. It makes more sense when he discusses the detractors who bring up specific arguments for limiting democracy.

For example, in the view that democracy begins with voters (not a view shared by the author), many voters do not participate. They don’t even know their own representative’s names. Some will even go so far as to say that many of these non-participants and low-information voters tend to be younger voters, women, and minorities. It’s not that they’re stupid; they’re simply too distracted to sort through the information, so… should they be included in the franchise?

One detractor made an argument for the establishment of an epistocracy (p. 50), that is, rule by the most knowledgeable.

Yeah, no ethical problems there.

I’m sure this detractor would count himself among the worthy electorate in his epistrocracy.

Nwanevu is not just using the detractors as punching bags. He is using this to form his own definition of democracy:

“Democracy isn’t about the will of the people winning out in a given collective decision. It’s about the right of the people to govern themselves through collective decision-making in the first place.” (p.68)

But democracy is more than voting, according to Nwanevu. It must also provide a mechanism to secure basic rights, give means to ward off domination by more certain groups over others, an acceptance of division and conflict, and a recognition that economic conditions “shape our democratic agency.” (p. 101)

He further argues that the United States is not a democracy, according to this definition, nor was it founded as one.

Part II of the book looks at specific institutions of the United States—the Senate, the House of Representatives, the Supreme Court, among others—and points to undemocratic aspects of each. It then offers ways these institutions might be made more democratic.

Part II also contains a full (long) chapter on a “democratic economy,” dealing with empowering the American worker through labor unions and eliminating right-to-work laws, among other, less routine mechanisms.

He uses Amazon as a case study. Jeff Bezos thanking his workers has always brought the following clip to mind:

Thoughts:

Both as a retired union member and as one who has called for the abolition of the Electoral College since a civics teacher explained it to the class long ago and far away, I confess that reading this part of the book turned me into a kid with my nose pressed up against the window of a candy store. Oh—wouldn’t this be cool! And that! Yes, please, may I have some of that?

More soberly, while I find some of his proposals, such as ranked choice voting, quite doable, others, such as making the Senate more representative of the population rather than the states, hit constitutional roadblocks. But frankly, I’d worry if I agreed completely with any author on the subject.

Alas! Things in the country are the way they are because they serve the interests of those with a bit more sway (i.e., money) than I have. And there is the enemy of us all: inertia. Yet, a girl can dream. And maybe shout a little in the meantime.

The subject matter is perhaps a little abstract at points, and I don’t think the book is for everyone, but I think it is an important book, with respect to a view of American history and to the present. The author explains without talking down to the reader. The writing is clear, amusing at times, and never dry. If the topic interests you, you should find the book well worth your time.

Bio: Osita Nwanevu (b.1993) is a contributing editor at The New Republic and a columnist at The Guardian. He is a former staff writer at The New Republic, The New Yorker, and Slate. This is his first book. He lives in Baltimore.

Title: The Right of the People: Democracy and the Case for a New American Founding

Author: Osita Nwanevu

First published: 2025

Length: nonfiction book

Review of “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie

The Stuff and Ramblings:

This semi-autobiographical YA novel centers on an adolescent young man called Junior growing up on the Spokane Reservation. Like the author, he was born with hydrocephalus and underwent surgery as an infant. Both also suffered seizures as children. Because he is not athletic, he is easy prey for bullies. He has one friend, however, Rowdy, who is both fearless and willing to knock the daylights out of most bullies.

Rowdy’s father is a mean drunk. Junior’s father also drinks but isn’t mean. Junior’s family, with its shortcomings, is loving. After a teacher advises him to leave the reservation, Junior tells his parents he wants to go to school in Reardon, an all-white school off the reservation, twenty-two miles away. They readily agree, though transportation remains an issue.

This draws immediate backlash. Others on the reservation see him as a white-lover and call him an apple, meaning someone red on the outside and white on the inside. Rowdy, Junior’s best friend, is especially hard on him, even though Junior tries to talk Rowdy into coming with him.

Early in the book, before he leaves for the off-reservation school, Junior talks about the effects of poverty. He had a dog named Oscar, who was the only being he could trust—more than any human. Oscar got sick. His mother finally had to tell him there was no money to take Oscar to the vet.

When his father got home from wherever, his parents had a talk. Junior’s dad got his gun and bullets and told Junior to bring Oscar outside.

“So, poor and small and weak, I picked up Oscar. He licked my face because he loved and trusted me. And I carried him out to the lawn, and I laid him down beneath our green apple tree. “(p. 13)

In describing this terrible loss, the author says:

“Poverty doesn’t give you strength or teach you lessons about perseverance. No, poverty only teaches you how to be poor.” (p. 13)

Another notable theme is alcoholism. After a series of tragic losses, Junior notes how many of them had to do with alcohol. One can be killed by drink without even imbibing if someone else gets behind the wheel drunk.

But I think by far the greatest underlying theme is the dual nature of Junior. He is an Indian, a self-designated “reservation boy,” but he also wants to build a life outside the reservation. This is indicated in the title “part-time Indian.” It also follows the relationship between Junior and Rowdy, where he concludes that Rowdy is his best friend, even if he hates him. The book is dedicated to Reardon and Wellpinit, the author’s “two hometowns.”

I did go on a bit…

One nice thing about the book is the many drawings by Ellen Forney, executed to look like sketches taped to walls or comic-book panels. Some give the impression of kid drawings, but there are also beautiful pencil portraits.

This book was the most banned and/or challenged from 2010 to 2019, according to the American Library Association. Really? I might have to re-read it in case I missed something. Okay, there were a couple of naughty words, and it mentioned that people gamble. It also discussed people drinking and doing stupid, sometimes hurtful and deadly things. But it advocates none of the above.

I have mixed feelings about the book. I enjoyed reading it, yet I hesitate to recommend it because of the allegations of sexual harassment made against the author, which I was unaware of when I chose this book at the library. Banning the book, however, would be pointless. It is a story worth reading.

Bio: Sherman Alexie (b. 1966) is a US writer, poet, and filmmaker who was raised on the Spokane Indian Reservation. Among his works are The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven (1993), which received a Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award and was adapted into the movie Smoke Signals (1998), for which he wrote the screenplay. Among his books of poetry are The Man Who Loves Salmon (1998), One Stick Song (2000), and Face (2009).

Several women have come forward with allegations of sexual harassment against Alexie.

He has apologized.

It is a sad business throughout.