Our Saturday night pizza and bad movie night resumes. This one catches Baron Frankenstein late in his career. He’s been run out of town, lost his creation, and is ready for a comeback. Can’t keep a good mad scientist down.

Plot:

A grieving middle-aged couple leaves their humble home to find a priest. They don’t notice the man (Tony Arpino) lurking in the woods outside. He’s not after them. While their young daughter walks through the dark house, and their recently deceased adult son lies with a crucifix on his chest, the man opens a window and drags the corpse through it. The little girl screams and flees through the woods, briefly meeting a silently sinister, well-dressed man (Peter Cushing), Baron Frankenstein. She keeps fleeing.

The body snatcher knocks on a door, where he’s admitted. Inside, the viewer hears the thumping of various scientific equipment. Beating organs hang suspended in jars. The body snatcher shows his curiosity about the goings-on, but Hans (Sandor Elès), the Baron’s assistant, pays him off and sends him on his way. Over the titles and some dramatic music, the Baron cuts out the corpse’s heart.

The bereaved couple and the little girl have not been idle but have summoned the priest, who then comes to the Baron’s lab and threatens the Baron, smashing some of his equipment. The Baron and Hans take off.

The Baron returns to his hometown of Karlstaad, intending to sell the furnishings of his chateau to buy more lab equipment. Ten years earlier, the authorities ran him out for assaulting a police officer and crimes against God.

They find a fair going on in the village. They also find the Baron’s chateau has been trashed.

The Baron and Hans have to return to the village for dinner. Until the police break up the show, a hypnotist (Peter Woodthorpe) calls our heroes up onto his stage. After attracting attention to himself, the Baron takes to the hills. It’s the only way out of the village. Of course, a storm overtakes them, but a deaf and mute woman (Katy Wild), seen earlier at the fair, comes to their rescue and shows them a shelter in caves in the mountainside. And guess what they find in those caves.

Thoughts:

From the lab where the Baron cuts out a heart to music in the beginning to the flashback of his creation of the monster before the good citizens of Karlstaad sent him packing, the sets in this flick are all elaborate and make all the appropriate buzzing and hums. How very cool. Some have more in common with Buck Rogers than the old Universal monsters. A dome opens with a probe reaching into the sky to attract lightning.

The monster (Kiwi Kingston) is not the traditional, green-skinned monster (copyright issues) but a clay-faced monstrosity that would give anyone nightmares. Peter Cushing is a great Frankenstein, a cold-blooded evil scientist who sees value only in his research and proving his theories about the origin of life. And he’s pretty pissed at the self-satisfied “Burgomaster” (David Hutcheson), who somehow ended up with a lot of loot from the Frankenstein chateau.

The Baron doesn’t count on the hypnotist coming into the picture as the one who can control the monster and thus control him.

While I would hardly call this a work of art, this scored high for me on the entertainment value. And the melodrama! The only thing missing was a burning windmill at the end.

I know these things are not everyone’s cup of tea, but if you enjoy monster movies, you should find this one fun.

Unfortunately, it’s not available for streaming for free. It can be rented or bought on YouTube and the usual places.

Title: The Evil of Frankenstein (1964)

Directed by

Freddie Francis…(directed by)

Writing Credits

Anthony Hinds…(screenplay) (as John Elder)

Cast (in credits order)

Peter Cushing…Baron Frankenstein

Peter Woodthorpe…Zoltan

Duncan Lamont…Chief of Police

Sandor Elès…Hans (as Sandor Eles)

Katy Wild…Beggar Girl

Released: 1964

Length: 1 hour, 24 minutes

Review of “The Invisible Ray” (1935)

This is our latest Saturday pizza and bad movie entry. I knew it was an oldie just hearing the dramatic music scored by Franz Waxman. The flick was a classic mix of science fiction and horror I’d never heard of before. The print and audio were nice and clear, though I didn’t notice a note as to whether the film had been restored.

Plot:

Dr. Janos Rukh (Boris Karloff) has invited two imminent scientists up to his hilltop home/mad scientist lair to demonstrate a newfangled telescope he’s developed, one that captures light from earth hundreds of thousands of years ago, and projects on a planetarium dome.

Arriving are the skeptical Sir Francis Stevens (Walter Kingsford) and Dr. Felix Benet (Bela Lugosi). Dr. Rukh’s much younger wife, Diane (Frances Drake), and his mother (Violet Kemble Cooper) welcome them. Sir Francis brings his wife, Lady Arabella (Beulah Bondi), and her nephew, the charming Ronald Drake (Frank Lawton). Ronald makes doe eyes at Diane.

Dude, she’s pretty, but, you know, she’s married—to your host!

The group assembles in Dr. Rukh’s lab. After the appropriate lights flash and buzzers buzz, they watch an ancient meteorite crash into Africa somewhere around modern-day Namibia—my best guess. Dr. Rukh is convinced the meteorite contains a new element. There are congratulations all around and the guests invite Dr. Rukh to join them on their expedition to Nigeria—a fair hike from Namibia.

Mother Rukh warns her son not to go to Africa because he will not find happiness there.

Thanks to help from locals, the expedition successfully finds the ancient meteorite and the new element, dubbed “radium-X.” Rukh harvests some secretly and finds his skin glows in the dark. After he pats a dog, it drops dead with a glowing handprint in its fur. Rukh concludes he’s been poisoned and seeks help in secret from Benet. Benet whips up a serum that controls but does not cure the poisoning. Rukh must continue to inject himself with it at regular intervals.

Back in Europe, Rukh realizes that radium-x is also something of a cure-all and uses it to heal his mother’s blindness. Diane has left him and is working for Lady Arabella. Rukh claims to accept that, but—

Dr. Benet has set up shop in Paris, also using the radium-x to cure various grateful patients. Rukh claims the invention and discovery should be his. He feels betrayed and sets out to kill all those on the expedition he feels have not given him his due.

Thoughts:

This movie gives the reader a lot to enjoy. The elaborate sets and mattes are nicely done. The dialogue is a bit overdone. The science is silly, even for 1935. But it’s nice to see Bela Lugosi playing a good guy for a change. Karloff may ham it up a bit, especially when going nuts, but this is part of the mad scientist schtick.

Speaking of 1935, when black actors were maids and chauffeurs, the black actors in this film are “native” Africans in loincloths who say things like (of a messenger), “Da boy run fast,” and “Yes, boss?”

Things play out to their inevitable end with few surprises, though the few that show up are nice. And the special effects, while they hardly hold up to present expectations, are plenty and decent for the time.

This movie is not great or particularly good, but it is enjoyable. It meets the fun criterion. I liked it, warts and all.

Unfortunately, I could not find this flick available for streaming. I’d suggest trying a library if you’re interested in seeing it.

Title: The Invisible Ray (1935)

Directed by

Lambert Hillyer

Writing Credits

John Colton…(screenplay)

Howard Higgin…(original story) &

Douglas Hodges…(original story)

Cast (in credits order)

Boris Karloff…Dr. Janos Rukh (as Karloff)

Bela Lugosi…Dr. Felix Benet

Frances Drake…Diana Rukh

Frank Lawton…Ronald Drake

Violet Kemble Cooper…Mother Rukh

Released: 1936

Length: 1 hour, 20 minutes

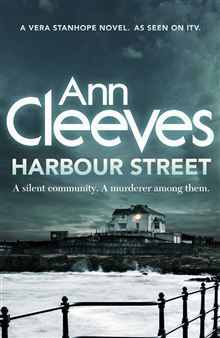

Review of “Harbour Street” by Ann Cleeves

Plot:

Detective Joe Ashworth is on the Metro, bringing his daughter Jessie home from a school program. The train is crowded because of the holidays. Joe noticed a couple necking. A well-dressed elderly lady boards, and Joe wonders why someone with money didn’t take a taxi.

Bad weather stops the train, and the passengers exit to busses. Jessie notices the well-dressed elderly isn’t moving. Believing she may have fallen asleep, Jessie approaches her to let her know they have to leave. Unfortunately, the older woman has been stabbed to death.

No one—not even Joe—noticed who might have killed the woman.

The police identify the victim as Margaret Krukowski who lived at a guest house on Harbour Street in the small town of Mardle run by Kate Dewer. Margaret was involved in an array of charity work, including a shelter for homeless women. Who would want to kill someone like her?

DI Vera Stanhope, Joe’s boss, arrives at Mardle trying to find everything about Margaret, convinced that understanding the background of the intensely private woman will lead to her killer. This proves difficult because people around her talk little of what they do know. Then, another murder occurs.

Thoughts:

This is the sixth in the Vera Stanhope series. Vera is an overweight woman of a certain age, whose late father used to engage in questionable activities, especially those involving protected birds. She routinely scolds those working for her, though Joe is her favorite protégé.

The setting is in northeastern England, and the book uses some dialect. Children are “bairns,” for example. This should not cause confusion for American readers, however, because the meaning is obvious from context.

One enjoyable thing about the books is that each character is drawn fully. The reader can see, hear, and often understand them by the end of the book. This adds a richness to the reading experience that many murder mysteries lack.

The mystery itself was not guessable—at least not to me. As often happens with Cleeves’ books, there are layers of generational history and small-town connections to unravel before anything makes sense.

Sadness comes across in events not connected to the murders. It’s as if sadness is part of the human condition.

I liked this book. If you are a Vera Stanhope, an Ann Cleeves, or a murder mystery fan, you should find this enjoyable.

Title: Harbour Street: Vera Stanhope #6

Author: Ann Cleeves

First published: January 16, 2014

Review of “How to Sell a Haunted House” by Grady Hendrix

This New York Times Bestseller by horror writer Grady Hendrix mixes horror, grief, and family trauma with camp. According to my exhaustive—or exhausting—reading of reviews on Goodreads, most people either love it or think it’s the stupidest thing they’ve ever read. I fall somewhere between.

Plot:

Louise Joyner returns home to Charleston after her parents die in a car accident. She dreads returning home, but she looks forward to seeing family—some of them. Her brother Mark is not among those she wants to see, but she has little choice. Mark was their mother’s favorite—he had everything handed to him, whereas Louise had to work for everything. They paid for Mark to go to Boston University. When he dropped out under mirky circumstances, they let him come home. Her parents bought wood for a deck Mark promised to build. The wood remains piled in the backyard.

The house itself gives Louise pause. Of course, there are her mother’s many dolls and the puppets she handmade for her puppet ministry. She finds a hammer on the kitchen table. The entrance to the attic has been hastily boarded up. Why would her parents do that?

Mark has hired a de-cluttering service to empty their parents’ house without consulting Louise because Louise hung up on him. Louise immediately objects. The owner of the service, unwilling to get in the middle of a family argument, dismisses his workers and goes home. Louise and Mark continue fighting.

But the puppets—

Thoughts:

In some spots, the author was having fun. Fellow puppeteers attended the memorial for Louise and Mark’s parents in costume. Louise is appalled, but the family congratulates Mark on his arrangements, telling him it’s what their parents would have wanted.

When Louise later hears noises in the house, she at first puts them down to squirrels in the attics. That’s why her father blocked the attic entrance, right?

In addition to the absurd, Hendrix shows the reader absurd violence. The puppets beat Louise. Taxidermized squirrels from a creche (which is gross and weird) attack her. She wallops them with a tennis racket and throws them in a garbage can.

What happens to Louise pales in comparison to what Marks undergoes.

Further menace appears, threatening Louise’s five-year-old daughter, Poppy. This struck me as sad, but through Poppy’s danger, Louise stands up to her family and learns an ancient family secret.

This is not a book for everyone. I enjoyed it. I could have done without some of the gory parts. The characters are flawed but sympathetic. Even the slacker Mark turns out to have more depth than a simple spoiled never-do-well.

Title: How to Sell a Haunted House

Author: Grady Hendrix

First published: January 17, 2023

Review of “The Black Cat” (1941)

Our last pizza and bad movie night of the year! We watched the flick with a black cat snoozing on the couch on his bed between us—after we finished the pizza. Unfortunately, the little guy can’t be trusted around pizza.

The Plot:

Elderly, infirm Henrietta Winslow (Cecilia Loftus) has called her family together to let them know the contents of her will. The news that the family has come together has also drawn a realtor, A. Gilmore Smith (Broderick Crawford), an acquaintance of Mrs. Winslow’s granddaughter Elaine Winslow (Anne Gwynne), and an antiques dealer, Mr. Penny (Hugh Herbert).

The groundskeeper (Bela Lugosi) tells them to leave their car outside the grounds. Since a car killed one of her (many) cats, Mrs. Winslow doesn’t allow cars on the grounds. The elderly woman’s caretaker, Abigail Doone (Gale Sondergaard), refuses to let Mr. Smith and Mr. Penny into the house, so they go around to a back entrance.

Mr. Smith is allergic to Mrs. Winslow’s small herd of cats and sneezes often. Mr. Penny chuckles to himself a lot, making high-pitched “hoo-hoo” sounds. Mr. Smith’s sneezing is far less annoying.

Mr. Smtih’s sneezing gives them away. They are soon ushered into the room where Mrs. Winslow hasn’t finished reading her will. She sits in her wheelchair with a Siamese kitten in her lap who plays with the papers she’s holding. The heirs seem content with their expected windfalls, except for Mrs. Winslow’s son-in-law, Montague Hartley (Basil Rathbone), who receives a mere $10,000. As it turns out, he has some heavy debts.

Later, Mrs. Winslow takes an unfortunate cat to the crematorium on the grounds. Many urns line the shelves. A statue of a black cat moves on its base, revealing the entrance to a secret passageway. Mrs. Winslow knows the person who comes but is surprised. She then screams in terror.

Her family finds her dead, stabbed with a knitting needle. Poor Grandma must have fallen and hurt herself. How tragic! How unlike murder!

Thoughts:

While Edgar Allen Poe is mentioned in the credits, this movie bears little resemblance to his short story of the same name. The two share creepiness—Mrs. Winslow’s cat crematorium and shrine, where she plans for her earthly remains to be entombed—are just one example. On the other hand, given her greedy family, I can understand why she prefers the company of her cats.

When it becomes apparent that Mrs. Winslow’s death was no accident (ya think?), Mr. Smith tries to determine who is responsible. Contacting the authorities is out of the question. Someone has cut the phone wires, and the bridge to town has washed away in the storm.

Many stock threats appear in the movie: a hand reaches out from behind a drape and empties something into Mrs. Winslow’s milk. Mr. Smith, on the hunt for the will, receives a stunning punch in the face from behind a drape. Sinister-looking groundskeeper Eduardo hangs around by windows, listening to conversations no one means him to hear.

Mr. Smith decides to find out who killed Mrs. Winslow. Unfortunately for him, he goes off half-cocked, annoying the family and making himself look like a fool in front of the girl he’s trying to impress, Elaine.

In the meantime, Mr. Penny is evaluating the various furnishings, “antiquing” them by damaging and destroying them. He also stumbles across a series of secret passages, not realizing what they are, and ends up in the bedroom of the sourpuss maid, Abigail. He finds her lying in a footlocker with a black cat…

Abigail recovers.

Much of the movie reminded me of an even more ancient flick, The Old Dark House.

In true murder mystery fashion, nearly everyone involved is not what the viewer expects. I did not guess the bad’un. While I liked it, I have to admit that many things are unlikely, and silly, and might try the patience of the average viewer. It can work if you know what you’re getting into and don’t take it too seriously.

The movie can be watched here.

Happy 2024 to all.

Title: The Black Cat (1941)

Directed by

Albert S. Rogell

Writing Credits

Robert Lees…(screenplay) and

Frederic I. Rinaldo…(screenplay) (as Fred Rinaldo) and

Eric Taylor…(screenplay) and

Robert Neville…(screenplay)

Edgar Allan Poe…(suggested by story by)

Cast (in credits order)

Basil Rathbone…Montague Hartley

Hugh Herbert…Mr. Penny

Broderick Crawford…A. Gilmore Smith

Bela Lugosi…Eduardo Vidos

Anne Gwynne…Elaine Winslow

Released: 1941

Length: 1 hour, 10 minutes

Review of “Now They Call me Infidel: Why I Renounced Jihad For America, Israel, and the War on Terror” by Nonie Darwish

The Stuff:

This memoir was written by Egyptian-American Nonie Darwish who spent her childhood in Gaza. Her father, Colonel Mustafa Hafez, served as commander of the Egyptian Army Intelligence in Gaza, then under military control of Egypt. Hafez was assassinated by the Israeli Defense Forces. Darwish’s brother was wounded in the same attack. The surviving family returned to Egypt. Darwish’s father was revered as a shahid, a martyr.

According to Darwish, her education and upbringing included a constant indoctrination of hatred against Israel and all Jewish people, though she admits she doubts she had ever met anyone Jewish.

She notes that while she came from a privileged background, most Egyptians live in dire poverty. Later, she married and immigrated to the United States. The move changed her perspective on many things. She met Jewish neighbors, who turned out to be something other than the slavering demons her upbringing taught her to expect.

She later becomes a Christian, a political conservative, a writer, and a speaker.

Thoughts:

Darwish writes in an easy style, albeit the text might have benefited from another pass through the typewriter. Picky me.

Despite the tragic loss of her father, she seems to have had a happy childhood surrounded by family. The reader understands how much she misses Egypt and Gaza. The author offers poignant memories and cute anecdotes, all the things that breathe life into a memoir.

As the daughter and niece of immigrants myself, I am fully in sympathy with her immigrant experience, and her longing for home while discovering new conventions in the United States.

However, her view of the world is simplistic. Islam is oppressive, teaches its adherents to hate, and leads to violence; the West is liberating—nothing in between. She touts the personal liberties offered in the United States without a glance at its history of racism. None of the Muslims I’ve known or worked with offered a threat to life or limb. The point is, I don’t see things as black and white as portrayed in the book.

It would be interesting to see what she has to say about the current Israel-Hamas War, with both sides responsible for many civilian deaths and committing what certainly appear to me to be atrocities. She was the founder of a group called Arabs for Israel and a director of an organization called Former Muslims United. The Southern Poverty Law Center has declared some of the groups and their affiliated groups to be anti-Arab and Islamophobic.

While she does come down hard on Islam in the book, she calls for its reform, particularly concerning the treatment of women. She also speaks of mosques as places of recruitment for terrorists—something that just ain’t so any more than a church recruits abortion clinic bombers.

Darwish’s story is interesting. The book is a quick read, but I can’t buy her worldview or politics.

Title: Now They Call me Infidel: Why I Renounced Jihad For America, Israel, and the War on Terror

Author: Nonie Darwish (b. 1949)

First published: 2006 (updated 2007)

Review of “Ring of Terror” (1961)

This is our latest Saturday pizza and bad movie entry, a black-and-white foray into college days. Uh-huh.

Plot:

The main story is framed by a graveyard keeper, R.J. Dobson (Joseph Conway), looking for his cat, Puma. He finds the feline by the headstone of one Lewis B. Moffitt (George E. Mather), with dates 1933-1955 and the engraving “I feared not.” Dobson laughs, turns to the camera, and spins the tale of Lewis’ life.

Lewis is a medical student dating a girl named Betty (Esther Furst) and pledging to an unnamed fraternity. He is hitting the books pretty hard. Nevertheless, he can still break away for a dance concert at the college cafeteria.

(College cafeterias must have changed from the 50s to the time I got around to going.)

Lewis is so gung-ho he even asks Professor Rayburn (Lomax Study) if he can assist him with an upcoming student autopsy. At first, the Professor demurs. It’s a job for seniors, who usually make excuses why they can’t—but since Lewis asked, well, okay.

Lewis isn’t afraid or squeamish. He explains this to Betty, too.

After the interminable autopsy, which opens with a glimpse into the “gastrovascular cavity” ( Ahem. And poor John Doe is still wearing his gold ring, huh?), Lewis has trouble sleeping. His roommate (Norman Ollestad) watches him having a nightmare and listens to him mutter, “Don’t turn off the lights.”

Is Lewis afraid of the dark?

Each member pledging the fraternity receives some task before being accepted into the brotherhood. One guy has to ask for a penny from each person on a particular street. Lewis—fearless Lewis—must retrieve the gold ring from the autopsy subject’s hand.

What could go wrong?

Thoughts:

This is a study in fear and the lies we tell ourselves. Unfortunately, several flaws make it hard to watch. First, the pacing is weird. Rather than ratching up tension, it wanders. The dance at the cafeteria is meant to be light-hearted but breaks action for some fat jokes, holding a heavy couple up to ridicule. The musicians are not playing the music heard. For example, the score includes a trumpet. The scene does not.

Lewis is portrayed as an intense young man, but clearly, the actor is much older than the twenty-something of the role. None of the actors are exactly fresh young faces.

Lewis spends the entire movie assuring everyone how unsqueamish he is. The dude doth protest too much, methinks. Only late in the story does he understand the meaning of his nightmares, which are connected to a childhood trauma.

The scenes are dark but not so dark it’s difficult to see what’s happening. The audio is a different matter. We watched this with Mystery Science Theater 3000, making it even harder. When I rewatched it on YouTube, it was still difficult to understand, particularly when many people were in a scene.

The autopsy that-would-not-end begins with Professor Rayburn telling the assembled guys (and they’re all guys) that this will be their first “gastrovascular autopsy” and showing them the “gastrovascular cavity.” I wondered what this was and looked it up. Humans don’t have them; they’re more common in flatworms and jellyfish, where ingestion and excretion occur through the same port. That’s exactly what it sounds like.

The guys were all medical students. The women were not. It was unclear what, if anything, they were studying. Their purpose seemed to be dating the various guys.

A better treatment of a similar idea—fear—is in the 1961 Twilight Zone episode, “The Grave.” While I wouldn’t call it high art, it did the one thing this movie didn’t do—it cared. The sad thing is, if the people making this movie had given a damn, it might have been a decent flick.

This gem can be watched here.

Title: Ring of Terror (1961)

Directed by

Clark L. Paylow

Writing Credits

Lewis Simeon…(original story)

Lewis Simeon…(screenplay) and

Jerry Zinnamon…(screenplay) (as Jerrold I. Zinnamon)

Cast (in credits order)

George E. Mather…Lewis B. Moffitt (as George Mather)

Austin Green…Carl

Esther Furst…Betty Crawford

Norman Ollestad…Lew’s Roommate

Lomax Study…Professor Rayburn

Released: 1961

Length: 1 hour, 11 minutes

Review of “America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines” by Gail Collins

This Stuff:

This is a survey of the history of women in America following European colonization until the end of the 1960s. It is broad, covering some four hundred years, and seeks foremost to cover the everyday life of women from all strata of society. What was childbirth like in colonial New England? How did one seek a mate in Victorian society? How did a woman (…and it was the woman for most of the time) arrange a household and raise children?

Author Collins shows outliers as well as everywoman. For example, a handful of women fought in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, some alongside their husbands. One, Margaret Corbin, took over for her husband after he was slain at the Battle of Fort Washington, was wounded herself, and received a military pension until her death in 1800.

It is stories like these that make the book eminently readable. Collins is at pains to include African American as well as different ethnic groups with the waves of immigration in the 19th century.

Thoughts:

It is the nature of a survey to be broad but not necessarily deep. In addition, the book is old enough now that some additional information has come to light. For example, Collins states that Margaret Corbin, she of Revolutionary War fame, was buried at the West Point Cemetery. When she wrote the book, this was the best information available. In 2017, it was discovered that the remains exhumed and reburied there belong to an unidentified male. The whereabouts of Margaret Corbin’s remains, assuming any exist, are unknown.

There are harrowing stories of women’s fight for suffrage during the 19th century. Some women in Great Britain went on hunger strikes and were force fed. Others, like Susan B. Anthony, voted before women were granted the right to do so, and simply refused to pay the fine she received. It didn’t change the law, but it makes for a good story.

One of the shortcomings of surveys like this is there is little room or time to examine many issues closely. On page 310, Collins writes:

“In the most spectacular act of British militancy, Emily Davidson threw herself in front of the King’s horse during the running of the English Derby in 1913, achieving instant if gruesome martyrdom for the cause.”

Davidson did indeed run onto the racetrack, carrying a banner with a suffrage message, and was killed, trampled by a racehorse. Feminists branded her a “martyr,” but precisely what happened is less certain. Recent analysis of newsreel film taken that day* shows her trying to tie a scarf to the horse’s bridle.

Her actions were foolhardy, perhaps. This article came out long after the book was published, but from the beginning, there has always been uncertainty as to what Davidson was doing. Collins makes no allowance for that uncertainty.

Initially, the press seemed to have recorded confusion.

A second example shallow information arises during the story of Collins recounts of Elizabeth Eckford (pp. 418-420), one of the Little Rock Nine who integrated the high schools in 1957, and Hazel Bryan Massery, who is captured in a picture screaming at Elizabeth. Collins quotes Massery shouting things like, “Go back to Africa.” Other sources expand on her comments: “Go home, nigger! Go back to Africa!” Massery later apologized. Collins writes, (p. 420), “the two women became friends.”

They did, for a while, but their relationship was complicated, as depicted in this article.

My understanding is that the two women have parted company but are not enemies.

I recommend this book because it is full of fun anecdotes, and it makes for great reading. Collins spent some time researching. Just the same, I would have to regard it as a starting point rather than a conclusion.

*The clip is easily assessable online. I chose not to watch it because I can’t watch a human being trampled to death, even though I know it was a long time ago and the troubles of everyone in the film (including the horse) are long over.

Title: America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines

Author: Gail Collins

First published: 2003

Review of “A Haunting in Venice” (2023)

For our traditional Saturday pizza and bad movie night, we watched a recent flick, an updated Agatha Christie murder mystery.

Plot:

Famous Belgian private detective Hercule Poirot (Kenneth Branagh), who emigrated to England, has lost his faith in God and retired to post-WWII Venice, no longer investigating, despite the long line of people seeking his help. Instead of a valet, a bodyguard accompanies him in the person of former police officer Vitale Portfoglio (Riccardo Scarmacio), who keeps the unwashed masses at bay, sometimes rather forcefully.

An old friend, Ariadne Oliver (Tina Fey), arrives and invites Poirot to a party and séance at a palazzo said to be haunted. Ariadne is a writer whose last few books haven’t done well. A famous medium, Joyce Reynolds (Michelle Yeoh), is coming at the behest of the owner of the palazzo, Rowena Drake (Kelly Reilly), a famous opera singer. Rowena’s daughter Alicia (Rowan Robinson) died by suicide.

In the spirit of Halloween, Rowena Drake is hosting children from a local orphanage for goodies, magic lantern shows of dancing skeletons, and a silhouetted puppet show, telling the gruesome story of how the palazzo came to be cursed. It was once an orphanage. When the Black Plague struck, the doctors and nurses abandoned the children they were supposed to protect. So now, their ghosts take their vengeance on doctors and nurses…

“But none of you are doctors or nurses, are you?” the puppeteer (David Menkin) asks. “So, let’s enjoy!”

When Poirot asks if such a horrible story isn’t too much for children, Ariadne tells him. “Scary stories make real life a little less scary.”

After the children go home, the séance begins. The medium is good, convincing even Rowena that she speaks in the dead Alicia’s voice. She throws in the tidbit that daughter Alicia did not die by suicide; someone murdered her.

Poirot exposes the medium as a fake, and she dies a gruesome death before the night is up.

Thoughts:

The film is based on Agatha Christie’s 1969 Hallowe’en Party but bears little resemblance to the book. It adds horror, a taste—a possibility—of the supernatural, and the richness of a setting in a medieval Venice palazzo. It deals with the horrors of war. While many scenes are darkly lit, these posed no difficulty in seeing the action.

Poirot uncovers a side plot of skullduggery in addition to the murders that is not strictly a red herring. Someone attacks him. Is it an attempt on his life or a case a case of mistaken identity?

Before her death, Alicia was experiencing mental illness and claimed to be hearing the ghosts of the children in the house. Did she indeed die by suicide, or did someone kill her? If so, for what purpose?

Another child, the precocious Leopold Ferrier (Jude Hill), claims to see and speak to the ghost children. Leo cares for his father, Dr. Leslie Ferrier (Jamie Dornan), a man broken by his experiences during the liberation of the death camps.

Even Poirot hears singing and sees a child trying to tell him something. When he turns, the child disappears. Was the child ever there?

The film is moody and haunting in the figurative sense. Scrambled or not, Poirot’s little gray cells see through to the truth of the things to point the finger at the bad’un. The answer is logical without being obvious. The bad’un gets their comeuppance in a scene that leaves open the possibility of vengeance from beyond the grave—or was it just a trick of the night, the storm, and Poirot’s eyes?

I liked this flick, as gloomy as it was. I didn’t mind the open-ended questions about the supernatural.

The film won the 2023 Hollywood Music In Media Awards (HMMA) for Best Original Score in a Horror/Thriller Film for composer Hildur Guðnadóttir. The music is fantastic.

This is too recent a work to download for free, but it’s available online for rent or purchase, and if you’re lucky, your local library will have a copy of it.

Title: A Haunting in Venice (2023)

Directed by

Kenneth Branagh

Writing Credits

Michael Green…(screenplay by)

Agatha Christie…(based on the novel Hallowe’en Party by)

Cast (in credits order)

Kenneth Branagh…Hercule Poirot

Dylan Corbett-Bader…Baker

Amir El-Masry…Alessandro Longo

Riccardo Scamarcio…Vitale Portfoglio

Fernando Piloni…Vincenzo Di Stefano

Lorenzo Acquaviva…Grocer

Tina Fey…Ariadne Oliver

Released: 2023

Length: 1 Hour, 43 minutes

Rated: PG

Review of “Empire of the Ants” (1977)

Now that I can eat pizza again and stay awake for a while, we resumed our Saturday night pizza and bad movie fiesta. This one was silly.

Plot:

Somewhere off the Florida coast, figures in red hazard suits dump barrels marked “Danger Radioactive Waste” and “Do Not Open” into the water. At least one barrel washes ashore near a rickety pier. Ants gather around, licking up some mercury- (and special effects-) looking substance oozing from the barrel.

Marilyn Fryser (Joan Collins), a sleazy real-estate developer, is gathering a tour of prospective buyers for a resort she’s building in the swamp, Dreamland Shores. Her salesman and present main squeeze is Charlie Pearson (Edward Power). Aboard the yacht that will take the marks—prospective buyers— is the captain, steely-eyed Dan Stokely (Robert Lansing).

Charlie and Marilyn take the group of eight or nine people on a two-hour tram tour of the resort that-will-be. (“The pool will be here. The tennis courts will be here…”). An alternative screen shows a black grid with a series of circles displaying the tram’s activities, like a bank of television sets in a store.

…Someone is watching our heroes. Someone who clicks…

When the group stops for a picnic under a tent, Thomas and Mary Lawson (Jack Kosslyn and Ilse Earl) wander off. Thomas is looking for something to prove this is all a scam. He finds PVC piping near a fire hydrant that he can pull out of the ground with his bare hands. “This isn’t connected to anything!” Thomas tells his wife.

“What’s that sound?” she asks.

Alas! They never make it back to the picnic.

Thoughts:

The movie bears little resemblance to the 1905 H. G. Wells short story of the same name that inspired it, outside of murderous ants. It’s hard to watch this and not see a little debt to the superior Them! (1954), a movie also involving mutated-by-radiation giant ants who like sugar but don’t mind munching people.

I was a little surprised at the PG rating. The film is quite bloody. I’d be careful about showing it to kidlets. There is no sex. One guy forces his attention on a young lady and gets kneed in the groin for his bad manners.

My biggest gripe with the film is that the characters are plot devices rather than people. The dialogue is as fresh as a carp left the counter for five days. Marilyn, for example, praises Charlie’s prowess “in the sack” within hearing of steely-eyed Captain Dan. The two biggest sleazebags abandon their respective partners to their fates with the ants.

Some minor gripes involve pacing: How long after eating the radioactive quicksilver do the ants grow to the size of milk trucks? The film doesn’t specify, but it implies all it takes is a weekend bender.

The special effects aren’t bad for the time. The ants are clearly crawling across pictures, which leads to some odd visuals at times. Less-than-perfect special effects don’t bother me.

An odd twist is the super-ants can control the minds of humans. The townsfolk must return once a week for their dose of mind-control spray. This leads one helpful farmwife to warn our heroes who have just escaped the horror of ants in the swamp, “Don’t let them take you to the sugar refinery.”

This really was a mixed bag for me. It could have been a much better film had it bothered to have more than stick figures for characters. The idea of psychological threat following prolonged harrowing physical danger is a solid one. Just when you thought it was safe—

However, if I laughed, it was more in delight than derision. Yes, it was hokey. Yes, it was silly. But it was a lot of fun. As for a recommendation—you won’t be disappointed if you go in with few expectations.

This movie can be watched (with a LOT of commercials) here on Tubi.

Title: Empire of the Ants (1977)

Directed by

Bert I. Gordon

Writing Credits

H.G. Wells…(story)

Jack Turley…(screenplay)

Bert I. Gordon…(screen story)

Cast (in credits order)

Joan Collins…Marilyn Fryser

Robert Lansing…Dan Stokely

John David Carson…Joe Morrison

Albert Salmi…Sheriff Art Kincade

Jacqueline Scott…Margaret Ellis

Released: 1977

Length: 1 hour, 29 minutes

Rated: PG