4) “Caterpillars” by E. F. Benson

The nameless narrator recounts how he sensed something was wrong the moment he set foot in the Villa Cascana—although it was a delightful house. When he saw letters on the table waiting for him, he thought perhaps there was some terrible news, but this was not so.

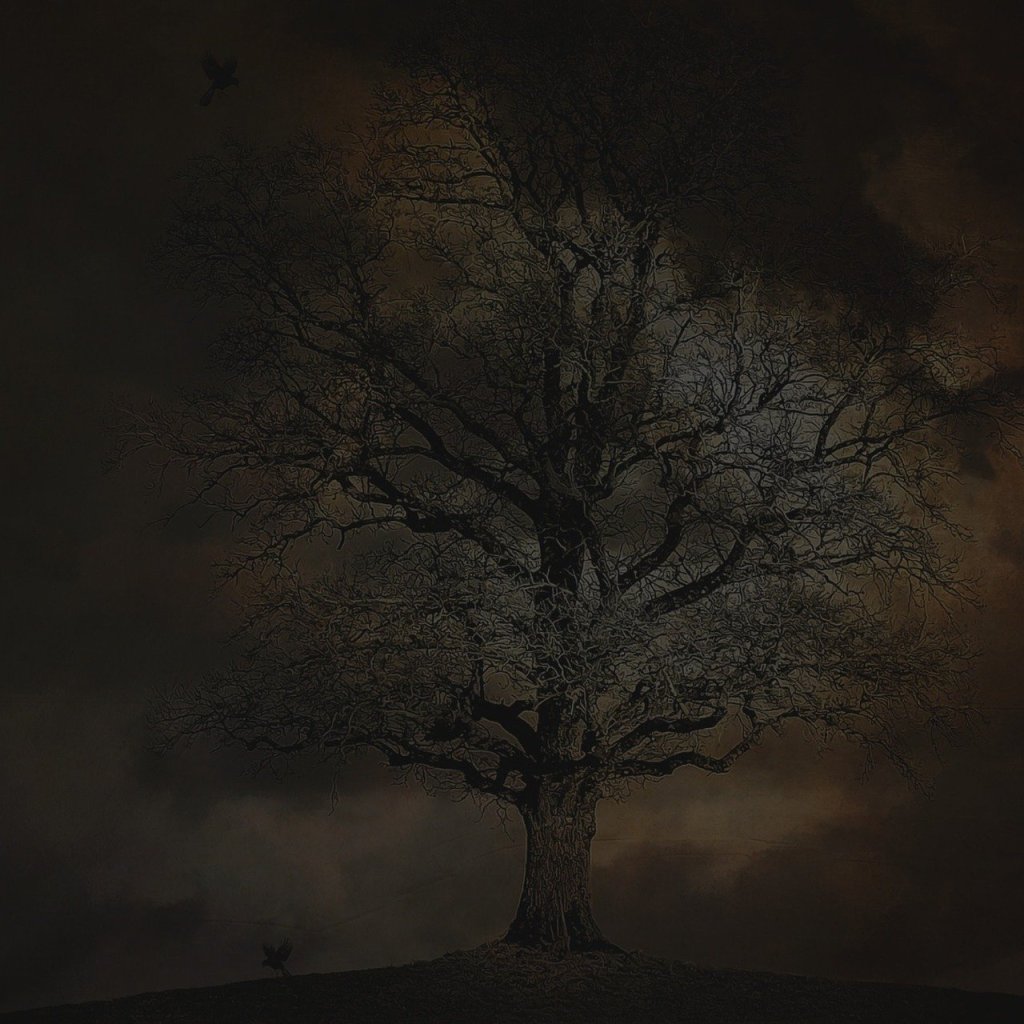

The hostess has left one room unoccupied. The narrator is assigned rooms at the top of the house. Though he seldom has trouble sleeping, that night he tosses and turns. In his dreams—if they are dreams—he dresses and descends the stairs. In the unoccupied room, he sees a writhing mass of what appears to be overgrown caterpillar-like beasts. They differ from caterpillars in some notable respects—their feet have claws, for one. When they approach him, apparently aware of him, he slams the door shut and flees.

Thoughts:

This is the stuff of nightmares. Is he dreaming? Are similar sequences, when he sees danger but can only stand on the staircase landing, unable to prevent it or even call out, a description of sleep paralysis? This is executed nicely and is terrifyingly told.

All this is undercut, however, by the story’s opening lines, which tell the reader that the Villa Cascana is being torn down. Whatever the narrator once saw it’s gone. And that other casualty (or maybe two), well, those poor souls. The news of the tragedy arrives via an innocent third party, who does so without understanding the narrator’s experience, adding to the horror.

This is a very short piece and can easily be read in a single sitting.

The story can be read here.

Audiobook available here Librivox.

Bio.: E. F. (Edward Frederick) Benson (1867-1940) was a British writer now known for his ghost and supernatural stories. He also wrote non-supernatural novels, including the popular Dodo (1893), satirizing composer and suffragist Ethel Smyth. Later in life, he wrote the Mapp and Lucia series, also non-supernatural.

Title: “Caterpillars”

Author: E. F. (Edward Frederick) Benson (1867-1940)

First published: The Room in the Tower and Other Stories (Collection), 1912